The writer and translator Keith

Gessen wrote last year of how western coverage of his country of birth,

Russia, was refracted through the distorted prism of the west’s own obsessions

in the 2000s and 2010s. While

self-identifying ‘left-wing’ writers in the west like Seumas Milne fall into

the same trap as Living Marxism magazine and Harold Pinter did over Milosevic in the

1990s –an intellectually infantile apologising for an authoritarian leader just because

the leader in question is “a counter-weight to the west” – Gessen pinpointed a more

subtle cultural trend that is separate from but co-exists with the

Putin-apologist contrarianism on parts of the western left. He sketched out the cartoonish depiction in

much western coverage of Russia – and the former Soviet Union as a whole –over

the last twenty years, shifting from Soviet-cliches to the ‘mafia state’ trope,

as one that took aim not just at Putinism but at Russians themselves, blunting

the complexities and realities of their experiences.

The piece came out around the same time as

the Calvert Journal ran an analysis

of how the western online media treated Russia and the former Soviet Union, at

least for the last decade up until 2014, when the Ukrainian crisis began: in

this period, Russia was downgraded from its twentieth-century status as ‘enemy', and repositioned as the ‘slightly unhinged stepbrother’ of the west – whose

excesses and idiosyncrasies (car crashes captured on dashcams, surreal wedding

pictures, women lacquered with industrial-strength make-up) the liberal west

was seemingly ‘allowed’ to laugh at without being accused of racism.

Cultural Russophobia and cultural Slavophobia

against eastern Europeans as a whole is pervasive and transmitted by cliche and tired tropes (and, as

Natalia Antonova has outlined, this thread in western thinking on Russia has in

turn been disingenuously harnessed by Putin’s regime to depict the west as

“Russophobic” because it does not

support Putin, while in fact it comfortably coexists with Putin’s ‘eternal

clash of civilisations’ worldview). And,

as Antonova has outlined, this Slavophobia is also highly gendered. The adverts for “Ukrainian brides” plastering

most tourism websites to Ukraine draw upon a series of deeply ingrained tropes

and imagery of the (European) ‘east’ in the eyes of the ‘west’. This stretches from the

sexist western fantasy of the ‘post Soviet woman’, hyper-sexual yet untarnished

by western feminism, to the stock role of the ‘baba’, the old woman who, if you

believed much western writing on the former Soviet Union, exists – without

back-story or human complexity – solely to provide comic relief, comically bad

amateur medical advice, and maternal encouragement to the young men visiting

her country. Its as though the classic

patriarchal virgin/ whore dichotomy is recalibrated so the two modes become

trashy/ hypersexual young women and comic ‘babas’, two options on the menu of

female experience.

“Ukrainian babes and comic old babas” might

have remained just another blindspot in a losing battle against the dominance

of cliché, but in a war – as the conflict in Ukraine continues – these

pre-existing tropes have become dynamic and loaded with power. In an interview with The Guardian last year, Oksana Forostina, the editor of Krytyka

journal, explained her frustration

with the western media in which “eastern European women are caricatured and

denigrated by their appearance – for wearing high heels and skirts, for example

[…] liberals wouldn't dare to do that to a Muslim woman who wore a veil." Yet the clichés of the ‘hyper-sexual, made-up

Barbie doll Ukrainian woman’ is pervasive, and fuels the ‘Ukrainian bride’

industry, which, as Matthew Kupfer has

noted, is particularly beloved of Men’s Rights Activist-style sexists

dismayed by the west’s move towards gender equality (who, in the process,

essentialise and deny the agency of Ukrainian women by transposing onto them

the image of the opposite-of-western-woman, fetishised through fantasy as ‘untainted

and obedient’).

Depictions of Ukraine in 2014 brought

together two strands. For reductivist tropes used to shorthand eastern Europe

in the west are highly gendered. And so is conflict. To claim that military conflict is gendered

is not to view it in terms of “men versus women” or a crude assessment of who

suffers more, but to make visible the gender binaries that become more rigid if

a society demarcates young men as ‘soldiers’, and if this then constructs or

reinforces a societal role of women as ‘carers’ and ‘subordinate helpers’. Extensive research has also shown that pre-existing

gender inequalities – particularly the levels of domestic violence in a

society – colour the severity of gender-based violence in war once the conflict

begins. In fact, academic Valerie Hudson

has argued that the levels interpersonal violence against women in ‘peace time’

are directly

correlated with the likelihood of the outbreak of conflict.

Acts

of humiliation

As the conflict in Ukraine develops,

although women have been present on the front line on both ‘sides’,

pre-existing gender roles as well as gendered tropes in the western imagery of

Ukraine, have transformed and mutated to the new, militarised context. A particularly uncomfortable example was the

pictures posted

of Irina Filatova, the new ‘Luhansk People’s Republic’ Minister for

Culture, variously topless and in a bikini, which spread around both Ukrainian

and western media in May 2014. There

were many layers to the discomfort: the fact that the pictures were taken from

Filatova’s private VKontakte profile (the post-Soviet equivalent of Facebook),

making them a kind of revenge-porn and an attempt to ‘shame’ a woman for being

a sexual person, and the joy with which (largely male) western

journalists sneered at her “trashiness” – a word, used for women, that

pinpoints the moment where misogyny and class-hatred align.

It is not an apology for the rent-a-warlord

‘leaders’ or fairground-mirror bizarre ideology of the Luhansk and Donetsk

‘People’s Republics’ to note – as, for instance, Keith

Gessen did in the London Review of

Books – that the alienation felt in the neglected Donbass region, which the

‘People’s Republic’ leaders were able to trammel into their agendas, stemmed

from a genuine sense of being on the receiving end of a kind of ‘social racism’

by the Kyiv elite. In a region where the

average wage was around 300 Euros a month prior to the conflict, sneering at a

young woman for being “trashy” – or for exercising her sexual agency in private

– seemed like the eastern European equivalent of the class-loaded hate-word

“chav.” Regional animosities were

playing out as Filatova’s bikini pictures were smeared across Ukrainian social

media, complete with captions about what a “whore” the woman in the photographs

must be – the equivalent middle-class southern English people sharing pictures of a

working-class Glaswegian woman and gleefully exclaiming that she looked like a

“slutty chav.” Yet the western media was comfortable harnessing this spectacle

and the complex power-and-powerlessness woven into it, because – transposed

over from its domestic context and into the global Anglophone media – it

reinforced predominant western tropes of eastern Europe, where the women are

‘trashy’, and the aesthetics are naff, but its okay for liberals to laugh at

that without being accused of racism.

There was an additional layer of discomfort

even for those who could smell the misogyny and class-tinged venom in the

situation: Filatova is not a person whose actions as a political figure can be

morally defended. Later in the summer of

2014, she was photographed leading a march as Ukrainian prisoners of war were

publicly paraded in an act of ritual humiliation – a practice, since the

conflict began, that has raised concerns of violations of the Geneva

Conventions’ responsibility to treat prisoners of war respectfully and

humanely.

The two scenes together – unsympathetic-figure Filatova’s

private bikini photographs shared around and ripped to pieces by internet

commenters, then her unrepentant participation in the humiliation of others as

the conflict developed – felt like an enactment in reverse of the French women who

were punished for sleeping with German men during the French Occupation by

having their heads shaved: the climate is created in which deliberate

humiliation of the other becomes acceptable, because they have committed injustices too, because they have humiliated you, so

you can use whatever you have over your enemy.

And humiliation is frequently gendered.

Yet there seemed to be a lack of

introspection in western responses to these scenes. There is much social currency – and many easy

internet clicks – amongst western liberals in mocking the garish, ‘trashy’

kitsch of the former Soviet Union, but still too often an insensitivity to when

this is ‘punching up’ and when it is ‘punching down’ – mocking the naff

glitziness of corrupt and authoritarian ex-President Yanukovych’s palace is

punching up at the powerful – is mocking the ‘trashy’ clothing choices of women

in a region where the average wage is 300 Euros a month, the same? Is using degrading gendered insults okay

because there are more important things to consider and “there’s a war on”? There is a frequent failure to maintain a consistent respect for human dignity.

'Fan art' of Nataliya Potklonskaya

'Fan art' of Nataliya Potklonskaya

Virgin/whore

– east/ west – Russia/ Ukraine

The dark underside of humanity that comes

out in Filatova’s uncomfortable role as both humiliated and humiliator also had

its opposite (although also on the same pro-Russian ‘side’), in the comedic

episode in early 2014 in which the Crimean Prosecutor General, Nataliya

Potklonskaya, was turned into a Japanese anime cartoon by her new global

‘fans.’ Although footage shows Potklonskaya

laughed along as she is shown the cartoon depictions of herself –

wide-eyed, pale and childlike – she did eventually exclaim in seeming

exasperation “I’m a lawyer, not a Pokemon!”

The anime cartoons seemed to play upon the same male western sexual

fantasy of Ukrainian women as both childlike (i.e. undemanding and untainted by

feminism) and hypersexual, which the multi-million pound ‘Ukrainian bride

industry’ draws upon to bring western men to the country.

The ‘Prosecutor General as anime cartoon’

incident in turn became a ‘comic’ story in the global media, marrying together

Ukraine’s pre-existing gender inequalities and essentialist tropes of

‘Ukrainian women’ residing in the western lens, while more complex realities

remained underreported even as the world began to take an interest in Ukrainian

society – such as the rates of domestic

violence in the country prior to the start of the conflict.

Yet, for all the attempts to treat the

post-Soviet space as ‘comic and unhinged’, the theme of violence against women

threaded through the escalating political tension, such as the incident

in April 2014 in which buffoonish populist Russian politician Zhirinovsky

appeared to threaten a female journalist with rape at a press conference, going

on to exclaim “you women of Maidan all have uterine frenzy”, and – to her

colleague – “stop interfering here, you lesbian.” The fact that there were almost no

expressions of solidarity from global journalists seemed to point to an

attitude of “that’s just how things are in the former Soviet Union, backwards

and sexist”, while the exclamations Zhirinovsky chose point to what Antonina

Vikhrest highlighted as the ‘tactical misogyny’ of Putin’s propaganda

machine.

As Vikhrest notes, a

so-bad-its-almost-funny “documentary” aired in on the Kremlin-backed NTV

channel in Russia titled

‘The Furies of Maidan’, which claimed to expose how women who were involved in the Maidan revolution that overthrew authoritarian President Yanukovych were psychologically

unstable, ‘disgustingly’ masculine harridans who were “aroused by fear.”

Stirring up hatred for Ukrainians and the

Maidan protests recalibrated the virgin-whore dichotomy, transposing it on to the

binary of ‘Russian versus Ukrainian’ – the pure versus the dirty – making women

the terrain on which delineation from the enemy ‘other’ is enacted.

Femen

and Ukrainian feminism: lost in translation?

Yet although there are glaring gender

inequalities in both Ukraine and Russia – and although the western lens of

viewing Ukraine has been largely un-empathetic to lived female experience as it

projects its own fantasies onto the country – there is also feminism. The Kyiv-based all-female band Dakh Daughters were for

many the musical accompaniment to the Maidan revolution. And, as in Egypt in 2011, female protesters

were integral to the struggle that brought down the corrupt and authoritarian

government. Societies are not monolithic

or internally homogenous, but engaged in internal conversations within

themselves – as much as conservative voices within these cultures erroneously seek

to depict local LGBT activists, feminists, and other progressives as ‘alien’,

‘elite’ and ‘imported from the west’.

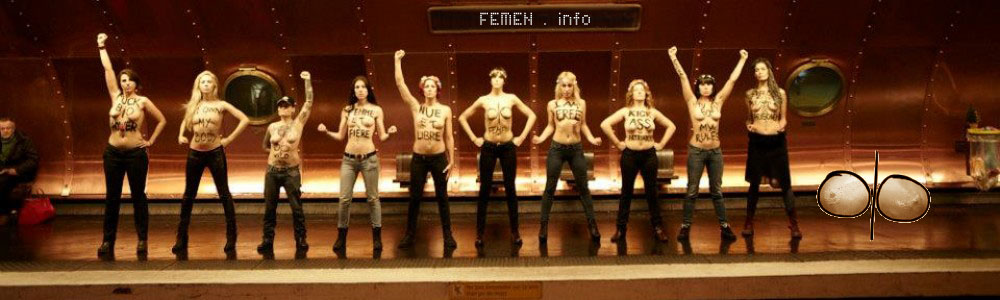

Yet when feminism in Ukraine is mentioned

in the western media, one strand of the internal conversation within the

movement continues to dominate the headlines – the tactics of Femen, the

self-identifying feminist collective that began in Ukraine, who use female

nudity ‘as a weapon’ in an attempt to draw attention to violence against women

and the brutalities of patriarchy.

There has been a significant backlash

against Femen from within the global feminist movement – and many other

Ukrainian feminists seek to distance themselves from the group. Most dismiss

the group as ‘colonial

white feminists’ or ‘racist feminists’, whose culturally imperialist

crusade to ‘liberate’ non-white and Muslim women denies the agency and humanity

of these women. Femen’s fixation on the

body and intellectually infantile ‘shock tactics’ seem, at best, an erroneous

attempt to use the master’s tools to dismantle the master’s house. At worst,

they are an embarrassing, racist distortion of feminism, who can then be used

to dismiss the legitimate social movement for gender equality.

Whilst acknowledging these criticisms,

writer Agata Pyzik has argued

that Femen must be contextualised as specifically eastern European – not simply as ‘white’ (and thus ‘imperialist feminists’, in the intersectional reading) but

also coming specifically out of an experience of being on the receiving end of the west’s

quasi-Orientalist fetishisation of eastern European women. Femen's fixation on the body as a terrain of

protest comes from their resistance to sexual exploitation, the sex tourism of

western men in post-Soviet countries that renders them ‘nothing more than

bodies’, existing to please men.

While Pussy Riot were conceptually stripped

of their feminist message when they became human rights heroines in the eyes of

the west, Femen have been conceptually flattened – with the strength with which

other feminists understandably condemn them as ‘white feminists’ and

‘culturally imperialists’ – so that the regional-specific context from which

their particular form of feminism has emerged from is lost in translation. None of which is to dismiss the criticism

that, outside of this context, their tactics are misguided and imperialist –or

that other Ukrainian feminist voices are sidelined by their headline-seeking

actions.

Tymoshenko

as Baba Yaga

The counter-argument that’s often drawn

when gender inequalities are highlighted – usually by those seeking to deny

that gender inequalities exist – is to point to the ‘exceptionals’, the

outliers. “How can the country be sexist

when it has had a female head of state?” is akin to saying “now Obama is

President, there are no racial inequalities in America”, yet politician Yulia

Tymoshenko, who lost the post-revolutionary election in 2014 after being

released from prison, is pointed to in conversations as proof that neither

Ukraine nor the western media’s treatment of Ukraine is sexist.

Like Filatova – or Sarah Palin, or Margaret

Thatcher – Tymoshenko is not

a person whose behaviour one necessarily wishes to apologise for. Yet disagreeing with her behaviour as a public

figure and her policy positions as a politician has often been seen, in both

the post-Soviet and western media, as a green light to criticise her on the

grounds of her gender – whilst simultaneously citing her as proof that gender

inequalities don’t exist. In the liberal

west, if you disagree with Obama’s position on, say, drone strikes, you would

still not get behind a cartoon that depicted him in racist tropes, yet pointing

out that Tymoshenko has been subjected to gendered insults throughout her time

in politics (such as depictions of her as a ‘Baba Yaga’ harridan, unnaturally

ambitious and vicious) is hard to sustain without being accused of defending

her politics.

It is important not to

draw binaries between ‘the backwards east’ and ‘the progressive west’ in its

treatment of women– one needs only look at Segolene

Royal’s treatment during her campaign for the French Presidency in 2007 to

know that female politicians in western Europe are subjected to sexist abuse. But discussions about Tymoshenko have often

shown that those who claim to have liberal, progressive politics are still

comfortable dismissing women they dislike as “bitches” and “hags.” All of which is underpinned by the

implication that women who hold power are somehow freakish and unnatural. And, as in the instance of Filatova’s

VKontakte pictures – if you don’t like the person, you can humiliate them any

way you like.

The

enemy woman

The gendered dimension of western

quasi-Orientalist visions of Ukraine – in which the women, ‘untainted by

feminism’, lack both human complexity and agency – has been married, in more

recent depictions of Ukraine, with the binary stirred up by the Kremlin

propaganda of ‘The Furies of Maidan’, in which Ukrainians and Russians are

positioned as opposites, just as the patriarchal virgin/ whore dichotomy

positions ‘good’ women against ‘bad’ women.

This constellation of gender binaries in a time when identity-lines

become more rigidly demarcated is reminiscent of the former Yugoslavia in the

1990s, in which the women of the ‘enemy’ ethnic group were targetted for both

their ethnicity and gender – or, rather, dehumanised for being the ‘enemy’

through humiliation and violence that played out in a gendered way.

The pre-existing gender inequalities in

Ukraine, both the levels of domestic violence and the power-dynamics of western

sex tourism to the country, are not priorities for a country at war – while, as

the conflict develops, nationalisms are stirred that generate identity

binaries, such as linguistic identity, that were previously not salient

identity fault-lines. Patriarchy and

nationalism do each other’s work for one another, nowhere more so than in

conflict.

Antonina Vikhrest, a Fulbright fellow researching gender issues

in Ukraine, has noted that reports have emerged that sexual

violence has occurred in east Ukraine as a result of the conflict, although

emphasises that the primary issue at present is one of documentation, as women

are often unwilling to come forward due to the social stigma of having been

sexually assaulted, a problem she encountered whilst researching at centres for

internally displaced persons in several Ukrainian cities. Vikhrest quotes

Human Rights Watch’s Russia researcher Tanya Lokshina, who explained that, in

the cultural context of the Ukrainian conflict, “rape is seen as something that

just brings shame to a woman…so out of concern for her security, her privacy,

for her future life, she stays silent.” Moreover, the lack of training on

the issue of sexual violence amongst humanitarian workers and journalists in

the conflict in east Ukraine has made accurate documentation of gender-based

violence more difficult. The new UN cross-agency Sub-Sector on Gender

Based Violence in Ukraine, established in December 2014, will focus on the

issue of sexual violence and the reports emerging from the conflict, but will

need to begin by addressing the lack of training and gender-sensitivity amongst

those working in the area affected by the conflict, which hinders accurate

documentation.

Yet the important work to be done on the gendered dimensions of

the Ukraine conflict lie beneath layers of quasi-Orientalist tropes in the

western ways of viewing Ukraine, false binaries, and silences. The lesson from the former Yugoslavia does not seem to have translated across -- pay attention to what happens to gender in war.

Via: opendemocracy.net

Short link:

![]()

![]()

![]() Copy - http://whoel.se/~xb6eS$5oA

Copy - http://whoel.se/~xb6eS$5oA