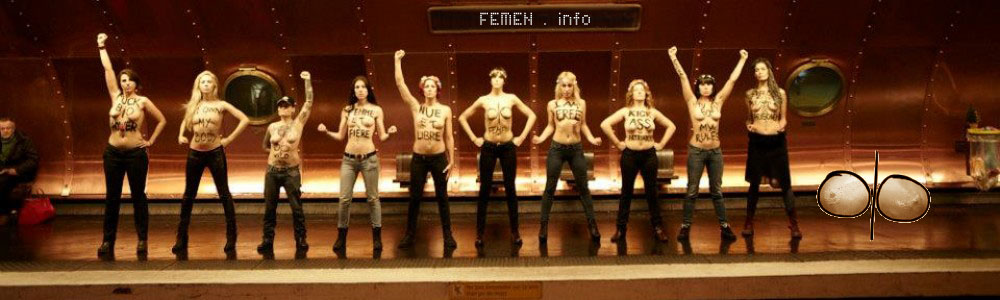

The story of Femen, Ukraine’s infamously topless feminist group, is totally riveting, but not for the reasons you’d think — i.e., its radical protest tactics, with bare-breasted beauties shouting incendiary slogans against prostitution and patriarchy before a gawking international press corps. As first-time Aussie filmmaker Kitty Green reveals in her compelling DIY documentary, Ukraine Is Not a Brothel, the problematic and at times downright contradictory structure of Femen in its early years speaks volumes about the corrupt and broken country out of which it took shape. Green, a Melburnian of Ukrainian descent, traded her job at ABC (Australian Broadcasting Corporation) for unprecedented access inside Femen, spending 14 months living with four of its activists in an apartment on the outskirts of Kyiv. As Femen gained international momentum for railing against its country’s authoritarian regime, its members were also forced to confront their organization’s own troubling contradictions and internal demons. Green’s powerful portrait of women putting it all on the line in the name of female emancipation uncovers a most disturbing truth: that an abusive male figure was calling all of Femen’s shots and cranking up the organization’s titillation factor. We caught up with Green at the SXSW Film Festival this week to talk about the role Femen has played in politicizing Ukraine’s youth, working in a constant state of paranoia (she was arrested eight times and abducted by the KGB), and her read on the dire situation the country now finds itself in.

As a Western woman from a progressive Australian metropolis, what was it like to immerse yourself in Ukrainian society, where the opportunities afforded to women are so limited?

When I arrived to Ukraine, everyone kept asking why I wasn’t married, why I didn’t wear pretty dresses, or why I wore black all the time! I had a family that would drag me to church so I could find a husband! Right away, I saw that imbalance, and the longer I stayed, the more glimpses I caught of the sex tourism. It’s not so much in the streets, but once you get a sense of how it works and the kind of men who gravitate around it, you recognize this darker, more insidious system at work. I was shocked by it, especially the equality thing—I never knew I wasn’t equal to a man. I’d be told, “why are you trying to be a filmmaker—just be a woman, just be a wife.” I had these strange and surreal conversations, which made me kind of angry.

You were brought on board as Femen’s official videographer, in exchange for access into the activists’ personal lives. What was it like to shoot their very theatrical protests, full of dramatic squeals, police repression and media pandemonium?

I was always more knowledgeable than the press—and they knew that. They’d all watch me to see where I went. When we crashed a Paris Hilton press conference, the media didn’t know Femen was coming until they saw me there with my camera. One of the girls just rushed the stage with her placard, got beaten down by security while Paris just stared at them, dumbfounded. We had to make fake IDs to get into press conferences, and do a lot of strange things to get the footage, but there was something about the adrenaline, the screaming and the danger of it all that had me hooked.

Would you refer to Femen as a performance art movement, similar to how Pussy Riot brand themselves?

No. I do think Femen is a form of street art and performance art, but their activism and political message are more important. They don’t really label it as art in that way. But when you see it on the street, it’s beautiful and theatrical and dramatic. The girls scream as loud as they can. The police are really aggressive in Ukraine, so it does unfold like a melodrama.

One of the many problematic issues about Femen that you bright to light is its approach to marketing and securing funds (which they’ve since dropped). Turns out this Svengali-type dude was pulling all the strings in the shadows – namely, “casting” pretty girls to be on Femen’s front lines and draw in more donations from men. What did you make of that strange paradox: combatting sex tourism…by tacitly encouraging it?!

A few days ago, a woman at a SXSW screening gave me $20, and told me to give it to the girls and say that it came from a woman! More women would donate to Femen if they felt a bit more included in the process. But at the time, with the organization being run by this guy [Ed’s Note: he’s no longer involved] with his marketing strategy, it limited their options in terms of funding. They got a lot of sex tourists funding them over Facebook, sending them checks, and it ended up being propaganda for sex tourism while also combatting it.

In the film, you expose this sinister puppet master running the whole operation from afar, and the girls’ very conflicted feelings about Femen’s structure. Have you been in touch with that man since recording your incriminating on-camera interview?

No…I’m terrified. He hasn’t seen the film; he’s apparently in hiding in Switzerland. I got one message through a friend, and he said: “tell Kitty not to tell the press I’m a tyrant,” because I was going around saying he was abusive. But I’m going to keep saying it, because it’s the truth! I’m interested to see what he thinks of the film.

Given that you’re now touring film festivals with some of the Femen ladies, how do they look back on the big identity crisis their organization went through?

It seems like so long ago. They dress differently now, many live in Paris, they speak English, they’ve travelled the world – they’ve come a long way. Inna [Shevchenko] is now the head of Femen France, so seeing that footage now, she hates it! It was a really tough process for them, because I asked the questions they didn’t want to answer. But I think they were ready to answer them because they wanted to move on. I guess asking those questions in some way helped instigate change.

But they also had to flee the country due to government persecution. Ultimately, do you think they want to return to Ukraine?

What’s going on in Ukraine now is horrific, but at the same time, they got rid of that president, and maybe that means the girls can eventually return. They’d love to see their mothers and grandmothers; right now they’re stuck in Paris. They’re living in squat and it’s really not as romantic as it sounds. They know that they’re needed [in Ukraine], in terms of their activism. They’re doing a lot of stuff in Paris for gay and lesbian rights and in support of Islamic women, but they know Ukraine needs them. They’re just trying to find their way back without getting stuck in jail for years.

Given the multiple arrests, intimidation tactics and thinly veined threats you were subjected to in Ukraine, are you surprised by the political crisis that’s unfolded?

Femen’s first protest was against [ousted president] Yanukovych on his first day in office – they called him out as a dictator. They were ahead of the times in pointing out how ridiculous this government was from the outset, and they were in some ways the first victims of his regime – they had to flee their own country because of persecution by the authorities. In our experience, getting arrested, watched, followed and spied on, my Facebook being hacked into, men standing outside our apartments… You could see the country was closing up and becoming more like Belarus, which is a dictatorship. It just had this oppressive vibe to it, like being trapped in an old spy novel.

What do you think might happen if/when Femen return from exile? Do you think more Ukrainians (especially women) would embrace them and their bold approach to activism?

Ukraine hasn’t seen the film yet, but I think Femen got people talking about feminism in the country, and that’s a big thing. Girls there now know what feminism is; they’ve seen Femen on TV. If it sparks debate, that’s already a great start in a country where those discussions aren’t taking place. But they’re not embraced yet; Ukrainians remain very skeptical of where the money comes from and why they’re naked. But I’d love to see what the reaction would be it if they returned. It’s a sad time for Ukrainians, but hopefully it also signals a change.

For more info about the documentary, go HERE.

[BULLETT]

More from Bullett:

Lena Dunham Says She’s ‘Nauseated’ by Woody Allen, ScarJo Not So Much

This Video Shows the One Thing Every Wes Anderson Film Has in Common

Sia’s ‘Chandelier’ Is So Good it Hurts

Open all references in tabs: [1 - 9]

Via: styleite.com

Short link:

![]()

![]()

![]() Copy - http://whoel.se/~6rzzk$4xZ

Copy - http://whoel.se/~6rzzk$4xZ