Another week, another heated debate over the tactics and language used by the feminist protest group Femen, which last Thursday launched an International Topless Jihad Day. The group, started in Ukraine, uses topless protest as a way to raise the profile of women's rights. The day of action was called in response to threats received by a Tunisian Femen activist, Amina Tyler, for posting topless pictures of herself on Facebook.

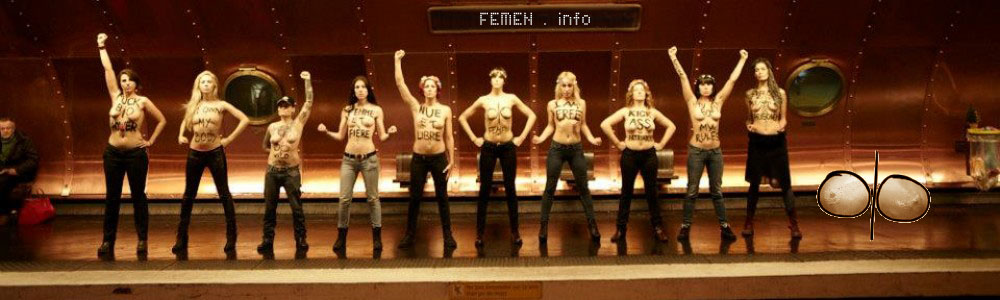

With slogans such as "nudity is freedom" and statements such as "topless protests are the battle flags of women's resistance, a symbol of a woman's acquisition of rights over her own body", Femen claims the removal of clothes in public as the key indicator of the realisation of women's rights and the most effective type of activism. Everything else is seen as not radical enough and failing anyway. By these standards, countries in north Africa and the Middle East and communities from those countries living in Europe are seen to be falling far short.

It argues that it is "transforming female sexual subordination into aggression, and thereby starting the real war" by "bare breasts alone". Using your naked body can be a legitimate form of a protest of last resort – there is a long history of using naked protest and the threat of it outside Europe. However, the way it has been used by Femen feeds into and reinforces a racist and orientalist discourse about the women and men of north Africa and the Middle East. With statements such as "as a society, we haven't been able to eradicate our Arab mentality towards women", Femen positions women of the region as veiled and oppressed by their men as opposed to the enlightened and liberated women of the west who live in a developed and superior society where they have the "freedom" to remove their clothes.

We know this is not true. Black women (and I'm using black as a political term to denote shared and continued experiences of racism and colonisation) are not all (and only) oppressed and black men are not all oppressors. Women in Europe, the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand do not live in a feminist utopia. There continue to be active and vibrant women's rights movements in Asia, Africa and Latin America. The feminist story belongs to all women, everywhere.

Femen's actions also come at a time of intensifying international backlash against women's rights that is increasingly being framed, perpetuated and accepted by male elites as rooted in "the west" and imposed on other countries in a form of cultural imperialism. Unfortunately, statements from white French women saying things like "better naked than the burqa" feed this narrative and are more likely to damage rather than support the struggles of the women they call their sisters.

Its defenders may say that Femen means well but having good intentions is far from enough. There is a long and problematic history of colonial feminism and the "good intentions" of outsiders using racialised notions to "save women over there". This actively causes harm, including when communities react to this by holding on to static notions of "culture" and "tradition" in the face of outside challenge as a way to resist colonialism and racism. Women's rights becomes the battleground with feminists from these communities and countries often left in a double bind, stuck between trying to reject racist ideas of black men and communities and challenging their attitudes.

We need a politics of international feminist solidarity that integrates a gender, race and post-colonial power analysis and takes its cue from the women affected and those who are already challenging gender inequality. As I have argued elsewhere, a more holistic and nuanced approach would consider how patriarchy combines with racism, neo-colonialism and global capitalism to create a fundamentally unjust world. We need to think about how our decisions, from where we shop to the issues about which we remain silent, affect the lives of women and girls in other countries.

Femen has continued to be unapologetic about its tactics and language and refused to address its blatant racism. When you are criticised by those "for" whom you are meant to be working, the response should be to think critically on your actions. Its latest piece offers no self-reflection or attempt to acknowledge criticism from women's rights activists from the region, only self-aggrandisement. To paraphrase Gayatri Spivak, white women will not save black women from black men. The role of feminists from outside should be to support the work of the women in the communities concerned, not add to the problem. International feminist solidarity is crucial but this is not the way to do it. A true ally does not use racism to attempt to defeat patriarchy.

Open all references in tabs: [1 - 8]

Via: guardian.co.uk

Short link:

![]()

![]()

![]() Copy - http://whoel.se/~DM5hC$2bz

Copy - http://whoel.se/~DM5hC$2bz