Inna Shevchenko, a long-standing Femen member, is sitting with me in a beach

bar in Venice. She is fully clothed, I should point out, and is joined by

her fellow activist Alexandra Shevchenko (not a sister, except in the

broader sense). Both women have a wreath of bright field flowers woven

through their silver-blonde hair: a traditional Ukrainian accessory for

young, unmarried women. Femen’s appropriation of this is, of course, ironic.

“Ukrainian women would wear these to attract a husband, but we are playing

with standards of beauty and sexiness,” Inna says. “We transform that. Now

I’m making you scared, my dear man – you don’t find me attractive any more.”

Russian President Vladimir Putin and German Chancellor Angela Merkel are

confronted by a topless Femen demonstrator in Hanover (EPA/JOCHEN LUEBKE)

With them is the Australian filmmaker Kitty Green, whose first feature,

Ukraine Is Not a Brothel, is now playing at the London

Film Festival. The film charts the early days of Femen, and

particularly their entanglement with Victor Svyatski, a Svengali-like

oddball who for years had been the group’s de facto leader.

Sviyatski certainly had an eye for a good publicity stunt and an ear for a

snappy slogan. But in front of Green’s camera, he admits he is less

interested in the group’s original message – drawing international attention

to the plight of young Ukrainian women for whom adult life is a binary

choice between domestic drudgery and the sex industry – than the medium

(naked girls running around outdoors). Since the film was completed, he and

Femen have parted ways.

In Ukraine is Not a Brothel we see Sviyatski berating the women, calling them

“weak”, “spineless” and “bitches”. In one sequence, he explains that he

actively discouraged protesters he deemed to be less attractive from taking

part in Femen stunts. Having a rampant misogynist at the helm of your

anti-misogyny group was, Inna and Alexandra admit, problematic, although

both say they are glad for the opportunity to exorcise this particular demon

in public.

“Making the film was like a confession,” says Alexandra. “We decided to trust

Kitty and to show everything. When we started Femen we were trying to get

advice from different people and we turned to Victor, who then started to

oppress us.

“He didn’t beat us, but it was psychological, and this film shows it can

happens everywhere – even to feminists who have decided to fight against the

patriarchy. And we should recognise it in the very moment it happens, and

fight back.”

Green first encountered Femen in early 2011, in a report in a Melbourne

newspaper. Enthralled, she quit her job with the Australian Broadcasting

Corporation, flew to Eastern Europe with a camera, and spent the next 14

months living with them on the outskirts of Kyiv and documenting their work.

To many westerners, topless feminism will sound at worst murkily cynical and

at best a contradiction in terms, and Green admits she was sceptical at

first about the group’s methods. This changed quickly, however, when she

arrived in Ukraine.

“Everything was startling for me,” she says. “I grew up in a very progressive

area of Melbourne, and all the women I knew worked. I knew there was such a

thing as gender inequality of course, but never appreciated what it might

actually be like. And it was only when I got to Ukraine that I realised how

big the divide between the sexes is.

“The women stay at home and aren’t allowed to speak up. And at the protests,

when the police see women who aren’t doing either of those things, they

react brutally. They would push the girls and shove them and throw me down,

and me too for being with them.”

Alexandra adds: “When men see uncontrolled naked women, that they used to see

only in their beds, out in the street, screaming against them, they are

afraid. They see that this regime that has stood for centuries is starting

to shake.”

For me, too, Green’s footage of the reaction to the protests is shocking.

Burly, uniformed men grab at the women’s limbs and hair, dragging them

across the ground and hurling them into vans, in which they are driven to a

police cell, and perhaps worse.

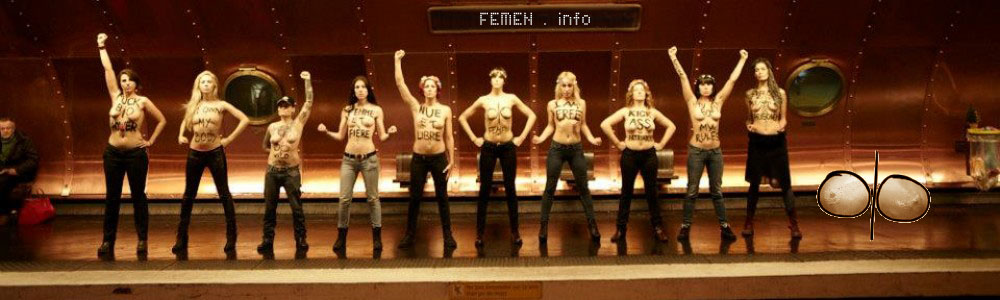

A Femen protest in Kyiv, Ukraine (REX)

During a 2011 action in Belarus, in which Femen protested the alleged

vote-rigging that had returned Alexander Lukashenko to power in that country

the previous year, three members including Inna Shevchenko were scooped up

off the streets of Minsk by men in dark clothing and driven in vans to a

forest on the Ukrainian border, where they were stripped naked, beaten up

and doused in oil. Green, who had filmed the protest, had her camera

confiscated and her footage deleted.

When I ask Inna about the ordeal, she talks about it in flatly matter-of-fact

terms. “Every day I get hundreds of death threats on my phone,” she shrugs.

“Every time we speak out, we get threats – ‘we will burn you witch’ or ‘we

will cut your head off’ or ‘a bottle of acid is prepared for you’. It’s the

lifestyle.”

But for them, the alternative is unacceptable. “If we hadn’t started Femen we

would be living the terrible life of normal Ukrainian women,” says

Alexandra. “Sexual slaves or domestic slaves, or slaves to our work.

“It’s easy to become a prostitute in Ukraine because what else is

there? When a young woman goes to an office to look for a job, they say we

are too young, or not educated, or even if we have a master’s degree we will

be pregnant or married in a few months.

“I’ve been told that if I want a job I have to sleep with the boss. I don’t

want to? OK, then I don’t get the job.”

Later that day, it occurs to me that these Ukrainian women stripping off on

their own terms might have something in common with the black Americans who

have ‘reclaimed’ racist language: something that once symbolised the sheer

hopelessness of their situation becomes a means to push back.

And of course there’s an element of playing the media here – but if they

hadn’t gone topless, would Femen have caught the eye of a young

documentarist on the other side of the planet, looking for a subject for her

first feature? And would you have just finished a 1,350-word article on

women’s rights in Ukraine?

Ukraine Is Not a Brothel is showing in the London

Film Festival on October 18 and 20

Via: telegraph.co.uk

Short link:

![]()

![]()

![]() Copy - http://whoel.se/~Tic8a$4Lw

Copy - http://whoel.se/~Tic8a$4Lw