For a group committed to exporting its radicalism globally, it's surprisingly inarticulate about what it stands for.

When the activist group Femen burst onto the Ukrainian protest scene in

2008, holding mud-wrestling matches on Kyiv's central Independence

Square to protest the country's notoriously dirty politics, I was

hopeful the stunts could succeed in kick-starting a serious discussion

about sexism and gender inequality, problems that continue to plague the

states of the former Soviet Union.

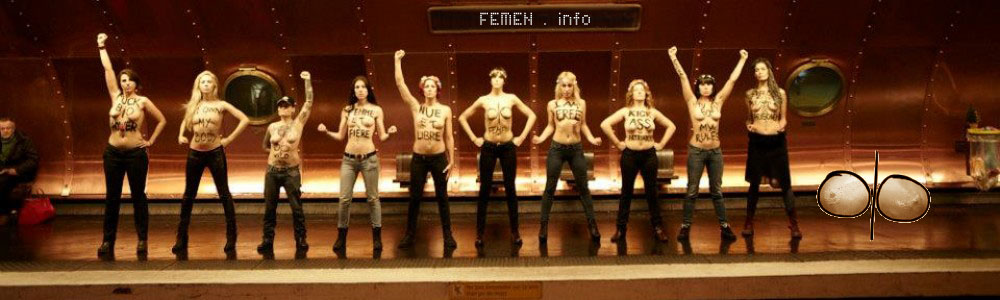

Four years and a new office in Paris later, the group, which professes

to use "sextremism" to fight against patriarchy as manifested by

dictatorship, the church, and the sex industry, more closely resembles a

girlie show. More flash than substance.

Femen has raised eyebrows -- and certainly provoked salacious grins --

with its topless antics, which have made it the most visible advocacy

group on women's issues. Now that Femen has successfully roped in the

international media with its stunts, it's worth examining what exactly

the "founder of a new wave of feminism of the third millennium" is

advocating or contributing to contemporary feminist discourse.

Ultimately, a message is only effective if it is clearly conveyed.

Though it would seem that there couldn't be a clearer message than one

written on nubile, bare flesh, a closer look reveals that what Femen is

actually proposing remains obscured.

In an interview

with Gazeta.ru, Femen activist Oleksandra Shevchenko stated that the

organization's goal is a "female revolution" but was sketchier on what

that actually entails. The group's website

offers little beyond somewhat garbled slogans and repeated references

to "hot boobs." A survey of their protests fails to provide much insight

into what the concrete goals are or what the contribution to feminism

may be.

In sum, there is little evidence of any of Femen's protests having

significant impact, either in terms of early local campaigns concerning,

for example, protests against the tradition in Ukraine of turning off

hot water in rotating districts of a city, let alone larger issues such

as the international sex trade.

'Pop' Feminism

Radical feminism has clearly changed since the first calls for women's

emancipation through suffrage were voiced in the first half of the 19th

century. Suffragettes were prepared to go to great lengths for the sake

of gaining basic human rights. As cigarette ads affirmed in the late

1960s, "You've come a long way, baby."

Twentieth-century feminist icons such as Gloria Steinem pushed the issue

of reproductive rights and entered the arena of LGBT rights, both of

which remain contentious in a number of Western countries. In the

Eastern Bloc, communism was supposed to be the great social -- and

gender -- leveler. Unfortunately, it didn't quite work out that way. Now, domestic violence and trafficking of women persist as serious social problems in many post-Soviet republics.

There are numerous international programs that address a variety of gender issues in all corners of the world, from La Strada International's work on human trafficking in Eastern and Southern Europe to the White Ribbon Alliance For Safe Motherhood,

which works to prevent deaths during childbirth. All of these programs

vie for public attention and funding. Yet "pop" feminism, at least in

the developed West, seems to be dominated by other concerns.

Some groups, including Femen, have been making the argument that the

deobjectivization of women can be achieved through in-your-face tactics

such as public nudity and overt sexualization. In 2011, a wave of "SlutWalks"

rolled through several North American and European cities. Launched in

Toronto, women tired of "being judged by our sexuality and feeling

unsafe as a result" encouraged other women to parade in various states

of undress, ostensibly to manifest their sexual emancipation.

Warped Logic

This trend could also be a sign of the times.

Desensitization to pornography

in Western culture, or at minimum its greater acceptability, has led to

a bit of warped logic that suggests that pole dancing can, in fact, be

empowering -- something I doubt even Aleksandra Kollontai would agree with. According to a recent piece in The Atlantic, pop singer Kesha "might be just what some of the 20th century's most famous feminist thinkers had in mind."

Perhaps the fault lies with feminists past who failed to make clear that

gender equality and ownership of sexuality and reproductive resources,

while certainly important elements of emancipation, are not the sum of a

human being.

Admirably, Femen has come out strongly against dictatorship,

Admirably, Femen has come out strongly against dictatorship,

increasingly a genuine issue of concern in Eastern Europe. The group

held -- or attempted to hold -- protests in Belarus and Russia. These

ended badly for the activists, as they discovered that security forces

in authoritarian countries are less polite and not quite as frightened

of female breasts as their democratic counterparts.

While not quite on par with its neighbors, Ukraine has been heading down

a slippery slope toward authoritarianism since the 2010 presidential

election. Though the group reports increased interest from the SBU

(Ukraine's security services), it continues to function without

incident.

With so many issues to tackle closer to home, Femen's decision to export

what it calls its "radical feminism" strikes me as disingenuous at best

and, frankly, somewhat cowardly.

This post appears courtesy of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

Via: theatlantic.com

Short link:

![]()

![]()

![]() Copy - http://whoel.se/~UjsyF$1xQ

Copy - http://whoel.se/~UjsyF$1xQ