The first step toward expanding beyond Ukraine took place after member Inna Shevchenko was forced to flee from criminal prosecution last August for chopping down a wooden cross in central Kyiv in support of the embattled Russian punk group Pussy Riot.

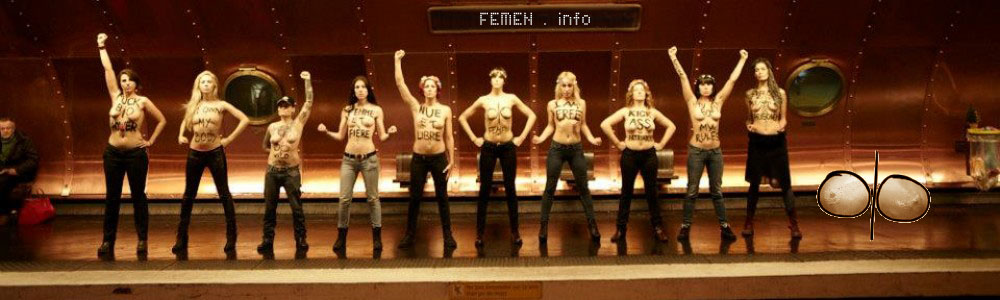

After making her way to Paris, she helped open an international office there for prospective European recruits. New members are trained in self-defense and protest techniques, and prepared for what Hutsol calls an “ideological war.”

France granted Shevchenko asylum last month, effectively formalizing FEMEN’s first foreign outpost.

Besides the Paris office, which Hutsol calls a “school” for rookie protesters that has hosted women from Mexico, Denmark, Turkey and elsewhere, the movement has representative groups in a handful of other countries.

These days, FEMEN is busy coordinating around 300 activists and maintaining constant contact with the media from its Kyiv headquarters.

Co-founder Alexandra Shevchenko (no relation to Inna) juggles a mobile phone and a laptop dressed in high heels and heavy make-up.

Between incoming calls, the 25-year-old defends FEMEN’s controversial strategy, explaining that the group chose provocative shock protests over launching a political party, an idea it briefly considered.

“Spreading a women’s revolution doesn’t happen in parliament, but on the streets,” she explains.

That choice has come with serious dangers.

On Saturday, Hutsol was allegedly attacked twice — outside her apartment and again in a cafe — by unidentified men. She was later seen with a black eye and puffed-up face. The same day, Kyiv police temporarily detained three other members, including Alexandra Shevchenko, and a Russian photographer as they prepared to stage a protest against a visit by Russian President Vladimir Putin.

They also said they were beaten.

The apparent blowback isn’t restricted to FEMEN’s home turf. Last month, a fire broke out in the group’s Paris office. Although police are treating the incident as an accident, the organization claims it was arson.

“We get death threats every day,” French activist Pauline Hillier told AFP the day after the fire. “Yesterday we received a message that said ‘burn witches.’”

Some of the roughest treatment followed one of the group’s first international protests.

In December 2011, three members, including Inna Shevchenko, said they were abducted in Belarus after staging a protest against the president, strongman Alexander Lukashenko, in front of the security service headquarters in Minsk. The women say security officers drove them to a forest, where they were physically abused and threatened with death for hours.

Despite the danger, Hutsol says such incidents help raise the group’s international profile and draw attention to its cause.

The Belarusian authorities “realized they couldn’t just whack us right there,” she said. “I mean, they could have, of course — but the whole world was watching.”

That kind of confidence will be needed for the campaign against FEMEN’s latest target, Islam, which has stirred the most controversy.

The catalyst was the recent jailing of the young Tunisian activist Amina Sboui, also known as Amina Tyler. She drew fierce criticism in March for posting topless photos of herself, one of which featured the phrase “F**k your morals” written across her breasts.

FEMEN rushed to back her, declaring an “International Topless Jihad Day” and slamming what they call Islam’s patriarchal repression of women.

However, many female Muslims said they found the move offensive, saying they felt their voices had been hijacked. The Facebook group “Muslim Women Against Femen” was launched shortly after and enjoys support from nearly 13,000 users.

A flurry of back-and-forth commentary in international media also followed, further fueling the debate over FEMEN’s controversial crusades.

“Femen undoubtedly raised a ruckus, but they cleared a path for the wrong kind of debate,” writer and activist Uzma Kolsy wrote in The Atlantic in May.

“If Femen aimed to shed light on injustices against Muslim women like honor killings or gender-related violence, they would have been better served putting their shirts back on, rolling up their sleeves, and supporting Muslim charities and social service organizations all over the world that are striving to remedy these social ills,” she added.

Meanwhile, the Sboui affair escalated. The Tunisian authorities arrested her in May after she wrote “Femen” on a cemetery wall. Prosecutors announced a number of charges against her, including “desecrating a cemetery” and “undermining public morals,” according to the human rights group Amnesty International.

When three European FEMEN activists staged a protest on Sboui’s behalf outside the Tunisian Justice Ministry in May, they were jailed for a month.

Although Sboui was cleared of a fresh defamation charge this week, she remains in jail and faces up to two years in prison.

Hutsol vows the fight will continue despite the physical and legal threats to FEMEN protesters.

“We want our Amina to serve as an example for other girls in Islamic countries,” she said. “For countries that are pursuing Islamization, she has shown that it’s possible, and necessary, to resist.”

Will FEMEN move on from the topless protests that have brought them international fame? Not likely, at least not soon.

“You can take away a placard,” Hutsol says, “but you won’t tear the skin off our bodies. Not yet, anyway.”

Open all references in tabs: [1 - 3]

Via: salon.com

Short link:

![]()

![]()

![]() Copy - http://whoel.se/~zgjlY$3tB

Copy - http://whoel.se/~zgjlY$3tB