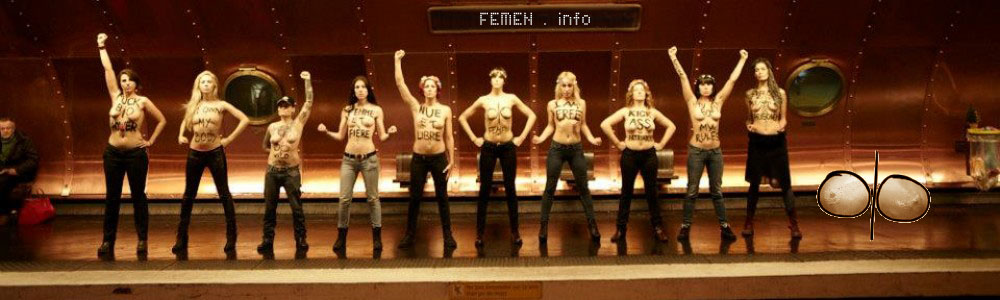

(WOMENSENEWS)--One attention-grabbing women's group on the Russian political scene is Femen, a constellation of topless protesters founded in 2008. Based in Ukraine, many of Femen's activists are Russian speakers, and the group has held actions in Russia as well as in their home state.

Whether or not Femen should be characterized as a feminist group is an issue of some dispute. The group consciously chose to display their naked breasts and, occasionally, more; one Femen poster with a nationalist message portrayed a woman with a Ukrainian flag on a stem held upright between her naked buttocks, with the slogan, "Hold on tighter." Yet Femen spoke out on a range of issues not difficult to recognize as within the feminist orbit. Their first protest (which was not topless) was held in 2008 under the banner "Ukraine is not a bordello" and was intended to protest against sex tourism in Ukraine--an issue to which Femen repeatedly returned, particularly with reference to the 2012 Union of European Football Associations soccer championships (held partially in Ukraine), which they believed would bring a flood of sex tourists to their country. Femen also opposed restrictions on abortion in Ukraine.

Anti-Putin Actions

A number of Femen's actions challenged Russian President Vladimir Putin's political legitimacy. In December 2011, following Russia's parliamentary elections, Femen staged a topless protest outside Moscow's Cathedral of Christ the Savior, with Orthodox crosses inked on their naked chests, holding signs aloft, reading "Lord, chase away the tsar!" Their aim was to condemn Putin for his government's authoritarianism and to support Russia's political opposition forces, who planned a mass protest in Moscow the following day. This presaged Russian feminist punk rock group Pussy Riot's anti-Putin protest inside the same Cathedral two months later.

In another protest against Putin's less-than-democratic regime, in March 2012, three Femen members appeared at the polling place where Putin had cast a ballot, presumably supporting his own presidential candidacy. The Femen activists removed their shirts, revealing slogans penned across their chests, such as "I'll steal it for Putin!" and "Kremlin rats!" and shouted, "Putin is a thief!" while attempting to steal the ballot box into which Putin had cast his vote. Police dragged the shouting activists away.

In August 2012, Femen protested in support of Pussy Riot by sawing down a wooden cross in central Kyiv that memorialized the victims of Stalin's political repressions. In a parallel to Pussy Riot's experience in the Cathedral, this action seemed to have motivated the Ukrainian Attorney General's office to announce its plans to prosecute Femen, whose core group then decamped for Paris.

Mixed Message

As with Pussy Riot, observers saw Femen as putting forth a mixed message. Using naked women's bodies to draw attention to political issues--in the aforementioned cases, lending their bodies to the Russian political opposition's cause--reinforced the notion that women's bodies were the main thing that women were capable of offering in the political marketplace.

The group also employed homophobia in their actions, referring to the Ukrainian Cabinet of Ministers as a "homosexual cabinet," for instance, while asserting Femen's own heterosexuality. Group members repeated the fact that they "love men" and did not protest for LGBT rights in Ukraine, so as to avoid being identified or linked with lesbians. Yet some observers argued that Femen combined traditional Ukrainian flower wreaths (symbolizing chastity) and nubile flesh in an effort to "parody the Berehynia-Barbie choices young women face" in contemporary Ukraine ("berehynia" is the Ukrainian term for a woman dedicated to caring for her family and home and stems originally from the name of an ancient female fertility deity worshipped in the region). From this perspective, the group was making an ironic challenge to women's expected roles in the post-Soviet symbolic field.

Feminist activists interviewed in Russia in 2012 offered diverse opinions and evaluations of Femen. While some found the group's protests "impressive" and "vivid," others were troubled by Femen activists' self-objectification of the female body and by their fairly uniform appearance. Though the group's actions occasionally included larger-sized or older women--one heavy-set woman played Belarusian dictator Lukashenko in a Femen protest in 2011, for example--the lion's share of the actions were carried out by women in their 20s who looked like runway models, fitting traditional "beauty standards." As with Pussy Riot, feminist activists questioned the content of Femen's actions as well as their methods, finding little evidence of a "feminist agenda" therein. As a member of the Moscow Feminist Group put it:

"In Femen's 'Ukraine is not a brothel' actions, is their message about being an object of sex tourism and sexual exploitation? No, the message is that 'our women aren't sluts,' something like that, with this unbelievable inflection of nationalism."

In other words, to some feminists, Femen's use of their bodies, as Mariia Dmitrieva has put it, did not aim to "deconstruct patriarchal femininity, but to use it and peddle it."

Reprinted with permission from "Sex, Politics, and Putin: Political Legitimacy in Russia" by Valerie Sperling, published by Oxford University Press, Inc. © 2015 Oxford University Press. The footnotes to this excerpt can be found in the book.

Open all references in tabs: [1 - 4]

Via: womensenews.org

Short link:

![]()

![]()

![]() Copy - http://whoel.se/~cOZab$5nO

Copy - http://whoel.se/~cOZab$5nO