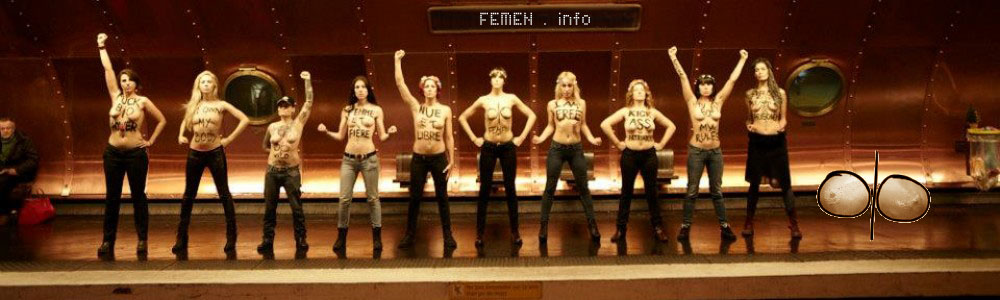

FEMEN has been making headlines with its provocative protests, yet support for them is not unanimous

On 29 May I watched a video of a FEMEN protest in front of the ministry of justice in Tunis. The protest was staged to support Amina Sboui alias Tyler, the first Tunisian FEMEN. The protest took place one day before Amina’s trial. The three protesters were European citizens: two French women and a German who came to Tunisia to support Amina’s case. They have been arrested and were charged for public breach of decency which in Tunisia is liable to a term of up to six months in prison. They have been sentenced to four months in prison for “public indecency, undermining public morals, and making noise disturbing peace”; however an appeal hearing is scheduled to take place on 21 June 2013.

Amina Tyler, a 19-year-old Tunisian girl posted last March topless photos of herself online with “my body is my own” scrawled on her body. She explains that the triggering event for her act was the assassination of the Tunisian leftist activist Chokri Belaïd, considered a political murder by some. She reappeared in May painting “FEMEN” on a wall near Kairouan’s main mosque, on the same day that the Salafist group, Ansar al-Sharia, was going to hold an annual meeting. She was afterwards immediately arrested. She was charged with carrying an incendiary object (a canister pepper spray). Sboui is still in custody waiting for the judge to take a decision regarding her charges.

Every time I hear about the FEMEN in the Arab World or elsewhere, I cannot help but be curious about their ideology and reasoning. The question for me is not so much to judge whether the FEMEN are right or wrong, good or bad from a moral standpoint, but rather to raise a debate as to the agency and weight of their actions and most importantly to keep the debate open and critical. There is not much reliable literature on the FEMEN movement. It is defined in its official website as follows: “FEMEN – is sextremism serving to protect women’s rights, democracy watchdogs attacking patriarchy, in all its forms: the dictatorship, the church, the sex industry.”

The FEMEN was born in Ukraine in 2008 to protest against prostitution and sex tourism: “with the slogan ‘Ukraine is not a brothel’ the women dressed as brides and ripped their clothes off, to protest against a New Zealand radio show that offered the winner the chance to come to Ukraine and pick a wife. The man never got his wife, and a movement was born.” They chose initially to protest in the way they did to symbolise the situation of Ukrainian women marked by poverty and vulnerability. These women only owned their bodies. They consider their bodies to be their arms. What is called “topless jihad” by the FEMEN movement is defined as “…self-determination over their bodies that they say is threatened by Islamism.”

Their means of protest is meant to function as an electric shock to raise awareness about women’s rights. They want to redefine nudity, in a sense. They argue they have to stand against patriarchal values and religions, but to what extent do they grasp the difference between religions and the use of religions in going against the universality of women’s rights? While, some Western feminists have welcomed the debate FEMEN has begun, as well as the attention they have brought to a cause that for decades has not dominated the news, support for FEMEN even in western capitals is not unanimous.

As for the FEMEN protest in Tunisia, it has led to controversial reactions to say the least; while some were trying to cover the three young protesters, others were trying to stop the journalists from filming. We could not help but feel the coexistent vulnerability and strength of the protesters, how they dared to stand where they stood and carry their message on their bare bodies in front of a mostly hostile audience? Press articles speak of an offended and scandalised Tunisian public. The FEMEN in Tunis confirmed what the global FEMEN claim regarding their methods: “This is the only way to be heard in this country. If we staged simple protests with banners, then our claims would not have been noticed.”

We cannot but be concerned about the mounting alienation which will follow; no matter how important FEMEN think their cause is, the way it is portrayed to the public gives rise to severe critics. This includes mounting violence but also lack of understanding – if not unwillingness – to try to understand what is really going on from the FEMEN standpoint. Amina Tyler unsurprisingly faced death threats coming from the different conservative strands of her society. Predictably the reactions of her own family following the incident were virulently violent to say the least, although she seems now to have the support of her father Mounir Sboui. He declared he is proud of his daughter, although the case is increasingly being politicised. He understands that even though her acts might seem “excessive”, she actually defended her ideas. However, reverse effects could also result from such protests. Anti-FEMEN protests were already witnessed on 30 May at Kairouan only hours before the start of Amina’s trial. Being by definition extremist or partisans of what they call sextremism, we could easily argue that extremism breeds and even feeds extremism, the kind of extremism that the FEMEN are claiming to battle against.

It seems to me legitimate to raise questions regarding the current context in Tunisia. What would the Tunisian FEMEN and/or their supporters answer to those who believe that there is no need for that type of nudity to protest; aren’t there other ways to join feminist activism, aren’t the FEMEN going too far perhaps? Don’t they fear falling into cheap, or even worse, free sensationalism? To what extent is an 18-year-old able to weigh in a sound manner her decision to join the FEMEN? What do the FEMEN reply to those who discuss the fact that the FEMEN activists get paid for their participation in protests? Allegedly, FEMEN activists are paid around 1000 dollars per month, which represents three times the average salary in Kyiv. Many questions arise regarding the sources of funding.

We cannot ignore the identity, cultural or even religious barriers proper to the Tunisian context, without contesting anyone’s freedom and liberty to dispose of their bodies as they wish. The body, a woman’s body is not neutral; it is definitely not an object in the sense it could be interpreted to be in FEMEN protests. By crossing certain barriers in a radical manner, which definition is adopted of concepts such as respect for a person’s body and his/her dignity? Dignity was at the forefront all throughout the different uprisings in the region.

The question seems relevant; prior to the first FEMEN protest, a member of the FEMEN movement stated the following, “FEMEN is planning the first topless action in an Arab country as a sign of a big changes… FEMEN is announcing the women’s spring that (is) starting in Tunisia.” What is sensitive is not so much being open about so-called taboos in society. Rather, I believe, what is at stake is the necessity to think about the kind of image, consistency, and content the FEMEN want to give to feminism, to this new wave of feminism, and more particularly to Arab feminism in association with the People’s Spring.

Via: the-platform.org.uk

Short link:

![]()

![]()

![]() Copy - http://whoel.se/~BKorX$3Pi

Copy - http://whoel.se/~BKorX$3Pi