Feminism has long been a dirty word in Russia. Just ask Svetlana Smetanina, a journalist for the state-owned Rossiyskaya Gazeta newspaper who, in a 2010 article, voiced an opinion that many Russians seem to share: women who self-identify as feminists are harpies, she wrote, “unfulfilled in their personal lives and bent on revenging themselves on men for their own unhappiness.”

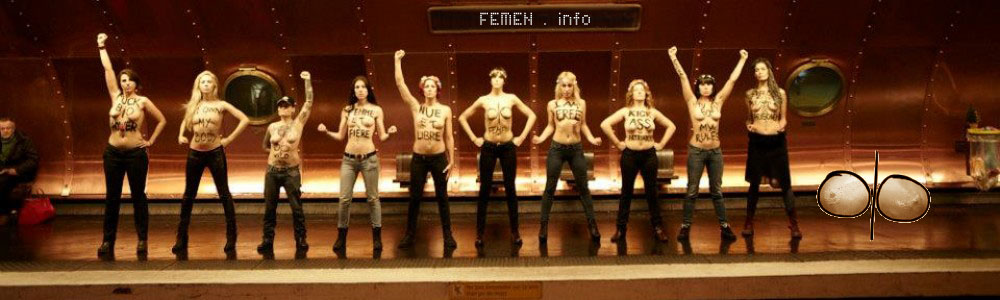

Smetanina’s op-ed is representative of the outright disdain in Russia toward feminists—an attitude on full display in recent months, crystallized in the Western mind by images of the punk art collective Pussy Riot being whipped by Cossacks in Sochi and of brutes in Crimea violently choking young, topless activists from the radical group Femen, whose bare-breasted protests against patriarchy and dictatorship (in this case Putin’s invasion of eastern Ukraine) have made them media darlings in the West. Love them or hate them, these women are at the vanguard of the fight against Putin’s repressive state at a time when the domestic opposition has been effectively neutered.

But radical feminism is very much in its nascent stages in Russia, so much that ostensibly educated women like Smetanina prefer to deny any reason for its existence. In her argument against the need for a homegrown brand of feminism, Smetanina invoked the Leninist past (“no discrimination on the basis of sex” during Soviet times) and a 2010 report by the World Bank on Women Business and Law which, she claims, found “women in Russia have more socio-economic and labor security than in the United States and in many countries in Europe.”

A common theme in Russia’s state media is that feminism is a Western plot, an imported ideology threatening the country’s patriarchal status quo. (Incidentally, the same argument was made about democracy, which explains why Putin and his allies continue to dismiss legitimate domestic dissent as Cold War-style meddling). When told to fight for gender equality, Smetanina maintains that Russian women “sincerely do not understand what people are talking about since they do not feel discriminated against as compared to their husbands.” Naida Azizova, a blogger for the Russian propaganda channel RT, agreed, saying that feminism is an idea “made in the USA” and that America’s bra-burning feminists have “only made their lives more complicated” in adhering to ideas of gender equality. The grim result, she laments, is that “gentlemen have given up their traditional behavior.”

Indeed, feminism is such a dirty word in Russia that Women in Russia, a “non-feminist” political party encouraging the “restoration of the family…through the family of Russia’s spirituality,” was founded in 2012. “We are not feminists,” party leader Galina Khavrayeva stressed, adding that they “have about 50 percent of male members and these are heads of our regional offices.”

Given these attitudes, it’s no surprise that Pussy Riot and Femen are far more popular in the West than in Russia. Both groups have become celebrities in the U.S., with their eye-catching protest tactics and performances dedicated to freedom from oppression. Indeed, the girls of Pussy Riot were treated like rock stars last month at a concert in Brooklyn organized by Amnesty International, just six weeks after they were released from prison. Madonna introduced them and Yoko Ono assured them backstage that “every step you take will change the world.”

While Pussy Riot is hardly an American plot, it’s true that the women have drawn inspiration from punk feminist icons in the West. “We were already interested in the idea of feminism,” Katia Samutsevich told VICE in December. “But we decided to find out if there were any feminist artists in Russia…Honestly, we searched for a long time and we couldn’t find anything. As we researched further and further, we learned about the second feminist wave in the U.S., which included punk feminism. We like this idea and started searching for punk feminist banks in Russia. And again, we didn’t find any. Maybe they exist, but they are not seen—which got us quite upset.”

And yet both Pussy Riot and Femen protesters are intent on effecting change from within Russia and Ukraine, not just from abroad. Nadya Tolokonnikova and Masha Alekhina, formerly of Pussy Riot, could have easily fled Russia for good after finishing their prison sentences, but instead have returned to “Mother Russia” to agitate for prisoner rights and to continue exposing Putin’s abuses of power. It should be noted that in doing so, these women are taking great personal risks with their freedom and even their physical safety. Last week, Nadya and Masha were repeatedly arrested as they protested against draconian jail sentences handed down to anti-Putin activists, and Nadya claimed that their whipping by Cossacks in Sochi left welts over her body. And a picture of a Femen activist being choked in Crimea went viral last week after the assault.

It’s not hard to see why Pussy Riot and Femen are threats to Russia’s machismo culture and fast becoming the bane of Putin’s existence. Ever since Pussy Riot (the name is enough to piss Putin off) was arrested in 2012 on charges of “hooliganism motivated by religious hatred,” the group has drawn international media attention to Putin’s authoritarian regime—and to the sorry state of gender equality in Russia. In the song “A Punk Prayer,” which they were performing when arrested in 2012, Pussy Riot urges listeners to “become a feminist / become a feminist, become a feminist.” The chorus to another song, “Kropotkin Vodka,” demands “the f**king end to sexist Putinists!”

The women behind Femen have also protested against Putin’s foreign policy toward their homeland and Russian sexism, and rallied around their fellow feminists in Pussy Riot. (For its part, the women of Pussy Riot have expressed both admiration and reservations about Femen: “Our opinion on Femen is a complicated story,” a Pussy Rioter using the pseudonym Serafima told VICE in 2012. “On one hand, they exploit a very masculine and sexist rhetoric in their protests—men want to see aggressive naked girls attacked by cops. On the other hand, their energy and the ability to keep on going no matter what, is awesome and inspiring”). Last week, Femen leader Inna Shevchenko staged a topless protest in New York’s Time Square against Russia’s occupation of Crimea, shredding the Russian flag and denouncing the country’s leader in front of a small group of reporters (“F**k Putin” was painted across her bare chest).

When topless Femen protesters mobbed Putin in Germany last spring, the Russian president dismissed the affront with thinly veiled condescension: “To be honest, I didn’t really hear what they were shouting because the security [guards] were very tough. These huge guys fell on the lasses. That seemed not right to me, they could have been handled more gently.”

But such condescension, once the norm in a country dominated by the Orthodox church, in which only 14 percent of parliamentarians are women, and where feminists are dismissed for “revenging themselves on men for their own unhappiness,” is finally being challenged by insurgent feminists like Femen and Pussy Riot.

For Putin and his ilk, feminist groups like Pussy Riot are contributing to “the destruction of the moral foundations of [Russian] society.” They accuse it of being “made in the USA,” brought into the country like a virus. But if those leading the feminist brigade contribute to the destruction of Putinism and the “moral foundations” of institutionally sexist Russian society, they may soon be celebrated as much at home as they have been in the West.

Via: thedailybeast.com

Short link:

![]()

![]()

![]() Copy - http://whoel.se/~Y0AmB$4wN

Copy - http://whoel.se/~Y0AmB$4wN