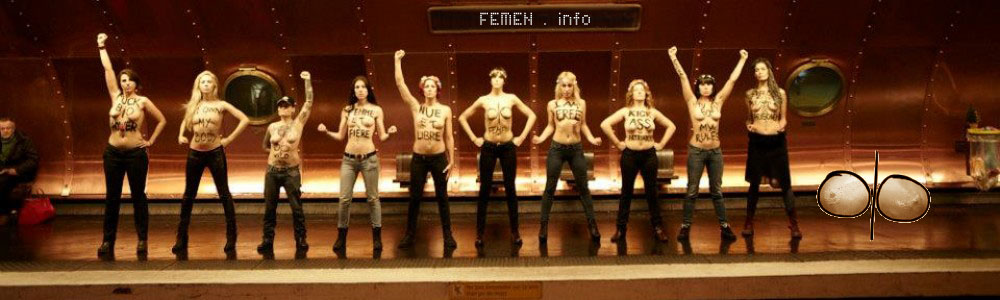

The final three films I saw at the 2014 True/False Film Festival all deal with images of women—images created by themselves, through media outlets, and even using such images as key evidence in court cases. Kitty Green's Ukraine Is Not a Brothel examines the exhibitionist feminist group Femen, whose members often go topless and paint messages on their bodies in protest of sex trafficking and sexist politics. Green's approach is to probe within the movement, interviewing women like Sasha or Inna (the film only identifies them by first name), who explain their devotion to Femen as a desire to turn the very objectification tactics used by patriarchy against itself: "No one wants to listen to a woman, but everyone wants to look." Thus, Femen only accepts/uses women who fit more conventional notions of beauty, which one member admits has "lost us a lot of good women."

Ukraine Is Not a Brothel initially looks to be a fairly standard explanatory documentary, but Green's interests, combined with Michael Latham's striking, often low-key cinematography, veer the film toward darkly comedic terrain as it's revealed that Victor Svyatski masterminded the whole operation—a patriarchy within a movement against patriarchy, and a paradox that Victor doesn't find altogether troublesome, even as he admits that he likely had a "subconscious" interest in forming the group because he thought it might get him laid. Victor isn't a sharp guy; in fact, the film opens with him wearing a rabbit mask, laughing goofily, and stating, "I am fucking rabbit." Green's critical eye replaces what initially appears as unwavering support to questioning the group's inherent motivations and how such a dubious leader could have lured so many women in—an answer which the women themselves don't reach a consensus on.

Green's questions reach rather ambiguous conclusions, though in the QA following the film, Inna, Femen's new leader, revealed that the group has since cut ties with Victor. Ukraine Is Not a Brothel ultimately exists in a representational space similar to the rad-fem tactics of Daisies or, even, Spring Breakers; in fact, the Femen women at one point don the brightly colored ski-masks made iconic by the latter, suggesting perhaps that they had the Harmony Kornine film in mind during production. That could cohere with Green's suspicions, it seems, as to whether patriarchy can be subverted by engaging (and potentially reversing) the very tactics which engender its sustainability. What Green lacks in resolution, then, Ukraine Is Not a Brothel makes up for by implicitly stating that image—whether self- or media-made—is all that ultimately matters.

Captivated: The Trials of Pamela Smart is solely about such questions. This HBO Documentaries film reopens the well-trodden case file to examine how media outlets turned Smart's image into myth and allowed news coverage of unfolding trials to become the ultimate postmodern theater. Jeremiah Zagar's film makes these intentions explicit by opening on a stage as the curtain draws to reveal a small television set. Zagar will return to this motif throughout, often lingering in highly-stylized, unoccupied domestic or public spaces with nothing but a TV running in the background. The ubiquity of media coverage continues even when no one is watching and the film positions the Smart case (and her cheerleader-turned-murderer image) as the impetus for the court-room and reality-television fervor that would ultimately replace conventional separations between public and private spaces.

At least the film appears to take such questions as its subject, but Smart ultimately remains the true subject, pleading her innocence, as the film unfortunately shifts into a rather straightforward case-file doc, replete with contradictory testimonies and requisite suspicion with the handling of the trial. Zagar weakly explains the trial's cultural influence by referencing Murder In New Hampshire: The Pamela Wojas Smart Story and Gus Van Sant's To Die For as works seeking to simply mythologize the case and manipulate its specifics to suit the purposes of a more digestible narrative. However, for anyone that's actually seen To Die For, these takes will read comprehensibly false, as Van Sant's satire of media-hungry obsessions gone awry forms a critique from within—much like the women of Femen attempt to do in Ukraine Is Not a Brothel. Zagar (and Smart), on the other hand, remains convinced that any such representations pervert the realities of the case—any semblance of understanding "what really happened." Of course, the irony is that escaping representation is impossible, since objectivity is an illusion; any mediated presentation necessarily takes a specific perspective.

Captivated largely misses these ironies, only making passing reference to the implications ("life as theater") or stopping so that interview subjects can state their lines with more emotion. These are rather glancing blows to a much larger indictment to be understood here, one that runs deeper than surface metaphors of media influence. Zagar's structure and politics devolve from questioning a particular kind of mediated fervor to concerning itself with more obvious issues of judicial malpractice.

Also an HBO Documentaries film, but to much more precise and nuanced effect, Cynthia Hill's Private Violence follows Kit Gruelle, a counselor for battered women in North Carolina, as she travels from county to county hearing stories from women who are trying to bring heavier charges against their assailants and, in some cases, family members of women who were murdered by their boyfriend or husband.

Kit's primary interest over the film is helping Deanna, who was kidnapped and beaten over the course of several days as her boyfriend drove her across country, bring more than misdemeanor battery charges against her assailant. Hill enters these difficult spaces with authenticity, interested in exposing questions like "Why didn't she leave?" as a gross, even sexist misunderstanding of the complexities faced by abused women. The difference between Rich Hill and Private Violence is that Hill's work lingers and probes with an urgent, comprehensive call to action, that doesn't abstract its unwavering social outrage by insisting on mythologizing those involved. Rich Hill and Private Violence is forced American myth; Private Violence is directive American trauma thinkpiece, insistent that its troubles can be confronted head-on.

True/False runs from February 27—March 2.

<!--

The final three films I saw at the 2014 True/False Film Festival all deal with images of womenimages created by themselves, through media outlets, and even using such images as key evidence in court cases. Kitty Greens Ukraine Is Not a Brothel examines the exhibitionist feminist group Femen, whose members often go topless and paint messages on their bodies in protest of sex trafficking and sexist politics. Greens approach is to probe within the movement, interviewing women like Sasha or Inna (the film only identifies them by first name), who explain their devotion to Femen as a desire to turn the very objectification tactics used by patriarchy against itself: "No one wants to listen to a woman, but everyone wants to look." Thus, Femen only accepts/uses women who fit more conventional notions of beauty, which one member admits has "lost us a lot of good women."

Ukraine Is Not a Brothel initially looks to be a fairly standard explanatory documentary, but Greens interests, combined with Michael Lathams striking, often low-key cinematography, veer the film toward darkly comedic terrain as its revealed that Victor Svyatski masterminded the whole operationa patriarchy within a movement against patriarchy, and a paradox that Victor doesnt find altogether troublesome, even as he admits that he likely had a "subconscious" interest in forming the group because he thought it might get him laid. Victor isnt a sharp guy; in fact, the film opens with him wearing a rabbit mask, laughing goofily, and stating, "I am fucking rabbit." Greens critical eye replaces what initially appears as unwavering support to questioning the groups inherent motivations and how such a dubious leader could have lured so many women inan answer which the women themselves dont reach a consensus on.

Greens questions reach rather ambiguous conclusions, though in the QA following the film, Inna, Femens new leader, revealed that the group has since cut ties with Victor. Ukraine Is Not a Brothel ultimately exists in a representational space similar to the rad-fem tactics of Daisies or, even, Spring Breakers; in fact, the Femen women at one point don the brightly colored ski-masks made iconic by the latter, suggesting perhaps that they had the Harmony Kornine film in mind during production. That could cohere with Greens suspicions, it seems, as to whether patriarchy can be subverted by engaging (and potentially reversing) the very tactics which engender its sustainability. What Green lacks in resolution, then, Ukraine Is Not a Brothel makes up for by implicitly stating that imagewhether self- or media-madeis all that ultimately matters.

Captivated: The Trials of Pamela Smart is solely about such questions. This HBO Documentaries film reopens the well-trodden case file to examine how media outlets turned Smarts image into myth and allowed news coverage of unfolding trials to become the ultimate postmodern theater. Jeremiah Zagars film makes these intentions explicit by opening on a stage as the curtain draws to reveal a small television set. Zagar will return to this motif throughout, often lingering in highly-stylized, unoccupied domestic or public spaces with nothing but a TV running in the background. The ubiquity of media coverage continues even when no one is watching and the film positions the Smart case (and her cheerleader-turned-murderer image) as the impetus for the court-room and reality-television fervor that would ultimately replace conventional separations between public and private spaces.

At least the film appears to take such questions as its subject, but Smart ultimately remains the true subject, pleading her innocence, as the film unfortunately shifts into a rather straightforward case-file doc, replete with contradictory testimonies and requisite suspicion with the handling of the trial. Zagar weakly explains the trials cultural influence by referencing Murder In New Hampshire: The Pamela Wojas Smart Story and Gus Van Sants To Die For as works seeking to simply mythologize the case and manipulate its specifics to suit the purposes of a more digestible narrative. However, for anyone thats actually seen To Die For, these takes will read comprehensibly false, as Van Sants satire of media-hungry obsessions gone awry forms a critique from withinmuch like the women of Femen attempt to do in Ukraine Is Not a Brothel. Zagar (and Smart), on the other hand, remains convinced that any such representations pervert the realities of the caseany semblance of understanding "what really happened." Of course, the irony is that escaping representation is impossible, since objectivity is an illusion; any mediated presentation necessarily takes a specific perspective.

Captivated largely misses these ironies, only making passing reference to the implications ("life as theater") or stopping so that interview subjects can state their lines with more emotion. These are rather glancing blows to a much larger indictment to be understood here, one that runs deeper than surface metaphors of media influence. Zagars structure and politics devolve from questioning a particular kind of mediated fervor to concerning itself with more obvious issues of judicial malpractice.

Also an HBO Documentaries film, but to much more precise and nuanced effect, Cynthia Hills Private Violence follows Kit Gruelle, a counselor for battered women in North Carolina, as she travels from county to county hearing stories from women who are trying to bring heavier charges against their assailants and, in some cases, family members of women who were murdered by their boyfriend or husband.

Kits primary interest over the film is helping Deanna, who was kidnapped and beaten over the course of several days as her boyfriend drove her across country, bring more than misdemeanor battery charges against her assailant. Hill enters these difficult spaces with authenticity, interested in exposing questions like "Why didnt she leave?" as a gross, even sexist misunderstanding of the complexities faced by abused women. The difference between Rich Hill and Private Violence is that Hills work lingers and probes with an urgent, comprehensive call to action, that doesnt abstract its unwavering social outrage by insisting on mythologizing those involved. Rich Hill and Private Violence is forced American myth; Private Violence is directive American trauma thinkpiece, insistent that its troubles can be confronted head-on.

True/False runs from February 27March 2.

-->

Via: slantmagazine.com

Short link:

![]()

![]()

![]() Copy - http://whoel.se/~KNy4E$4tM

Copy - http://whoel.se/~KNy4E$4tM