Today, FEMEN describes itself as a radical movement opposed to "patriarchy" and its three manifestations — "the sexual exploitation of women, dictatorship and religion". Why are women on the forefront of the radical protests movement across the globe? And do the topless warriors of the 21st century have anything in common with feminists of the previous epochs? What is the role of modern feminism? How are women using the theories and practices made famous during the 1960s to advance the position of women and girls in modern society? How different is the agenda for women in various countries and why American women have not taken to the streets in numbers as large as their sisters in other parts of the world?

Guest in Washington DC:

- Soraya L. Chemaly, a feminist critic whose writing focuses on the role of gender in politics, religion

Guests in London:

- Julie Bindel, political activist and founder of the group Justice for Women

- Anne Dickson, Psychologist and author of 'A Woman In Your Own Right'

Guest in Moscow:

- Natalya Antonova, current acting editor-in-chief of “Moscow News “

The discussion will be hosted by Jamila Bey.

Women around the world are naming and claiming the mental a feminism. And they are demanding that they be taken seriously and also that they be considered part of the larger world. Bare breast and twitter accounts are markers of a new wave of feminism younger women across the world are taking part in.

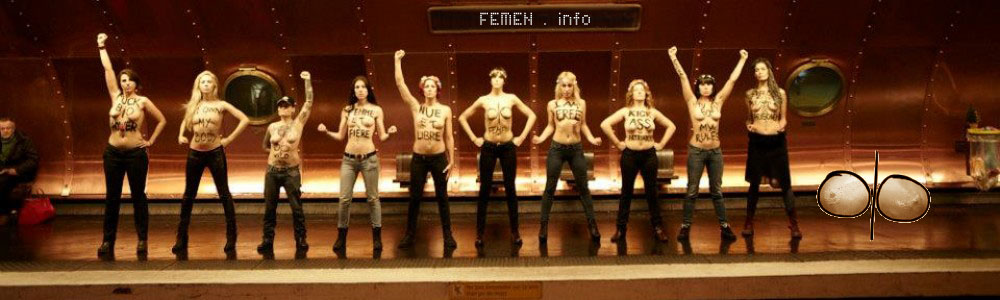

One particular group that we want to discuss today is FEMEN. They are based in the Ukraine and Paris and they are not afraid of displays of sexuality and femininity and protest the religion oppression, sexism, patriarchy and other anti-feminist issues that women around the world face.

These women are enjoying a far broader reach than their foremothers thanks to social media and modern culture that encourages sharing and mass impromptu organizations and events. FEMEN are taking the conversation about the role of women in the world to a far larger platform that has been seen.

What is the role of feminism today?

Soraya L. Chemaly: I think that women and girls are using the Internet as the transformative social justice tool. And so, there is a very busy active vocal Internet presence on the social media of people engaged in the fight for women’s equality, parity and liberation. So, in doing those things, as you pointed out, there are leveraging tools that were used earlier but in new and different ways. That is all very good. But, possibly, not very good part is that we don’t do a very good job of educating people about the history of women’s movement and feminism, so we see a lot of recreating the wheel that happens.

Give me the example of the recreation of the wheel?

Soraya L. Chemaly: I think we have seen recently with the explosion of the Twitter hash tags “solidarity is for white feminists” related issues that we have perennial problems that are disheartening because you would hope that something like racism within feminism would be something at this point in time that wouldn’t cause this kind of catalytic global response.

But I think a lot of the issue at hand is that the newer generation, the younger generation of activists and women, as well as their older counterparts, are seeing similar patterns, similar institutionalization of problems that we have because at every single stage we start from scratch, we need to be able to educate people on social justice issues related to race and to gender, and sex and sexuality when they are much younger.

As it is, we, who are interested as feminists, somewhat make it up on our own. We get to college usually and at that point we seek out the kinds of classes that we want. And that is if you are fortunate enough to go to college and be able to afford college. If you are not in that situation, and you are creating your own education as far as feminism is concerned, I think across the board, regardless of where people fall on the color or the class spectrum, there is a problem with the lack of consistency that cobles us, and the lack of history.

FEMEN have got a range of women who are protesting, giving support to women in other places who are protesting. FEMEN has been very active in making sure that women who have to be veiled against their will, girls who are kept out of school – those issues are brought to a larger, more moneyed and more educated audience around the world. But FEMEN has just lost one of their major allies with some of the same claims of Islamophobia that we saw here in the US when black women started leaving feminist organizations over claims of racism. Old is new again.

Soraya L. Chemaly: I think FEMEN is jarring on lots of levels to many people. The thing I like about FEMEN is one of their original ideas, which is the use of women’s bodies to portray strength and anger. The question with FEMIN is really whether any women living in a patriarchal culture can claim their bodies for their own uses.

We see a lot of FEMEN, we see a lot of topless beautiful angry young women in the media because they serve very mainstream ideas about sexualized women’s looks. We don’t see pictures of very long history of women protesting topless for example in lots of African countries over the period of colonialism and we don’t see pictures of older women protesting topless.

There are a lot of instances in the history of feminism for a very long period of time where nudity is claimed by women to confront patriarchy. But I think the problem with FEMEN from the perspective of their anger and their nudity is also a problem of media monopoly – who is making decisions about what we see in media. That is separate from FEMEN’s own internal composition issues. That is more a matter of media representation.

London

How is the language of feminism and FEMEN considered in England?

Julie Bindel: I’m 51, I’ve been active in women’s liberation movement here in the UK since the late 1970s. We are proud of the young women being so direct and taking direct actions tactics, and being very clear about issues that are difficult for which you get a lot of disagreement such a pornography, the sex industry, and that being very clear that these are very exploitative industries and that we are not going to put up with sexual harassment etc. In a way we are one movement.

But each new wave of feminism seems to reinvent the wheel, make some similar mistakes or rather have to sort out a mess left from the older wave. But what also tends to happen, and I put FEMEN in this category, is that they reject some of the things that we got right, some of the groundwork that we achieved, which we really don’t have to go over again and again.

One of those issue is that until we can properly challenge the growing sexualization of women’s bodies, particularly young, white, conventionally attractive skinny women, you can’t really use getting your breasts out in public as a protest because men are going to love it, men have grown up on MTV and pornography and they see young skinny white women constantly getting out their breasts and so I am not sure it works.

I love their approach, I love their sentiment, and I love the idea that women’s bodies can actually be used to shock men who wish to see as asexual beings but I don’t think you can do it under the system of patriarchy and get away with it. I don’t think it is effective.

Moscow

How the FEMEN is being looked at in Ukraine and in Russia?

Natalya Antonova: I interviewed their leader, back in 2009 when they were just starting to be famous and she said “Look, we are not girl-scouts. If we were trying to be all modest and non-provocative, no one would pay any attention to us”. The view of feminism, both in Russia and in Ukraine, is that feminism is for the ugly women who can’t get a man. And while that perspective also exists in the US, I would argue that in Russia and Eastern Europe it is much worse, it is much more pervasive.

So, they immediately from the start had this tactics of “we are not going to go the traditional route, we are going to be naked, we are going to be provocative, we are going to shock people, we are going to insult them to their faces”. I feel that while in the West people are shocked by it, here there is more amusement directed at them. It is sort of like it is not really anything different from what you’d see on the music channel.

Sure, they are naked, they are interesting in the sense that they are willing to use their bodies, willing to put themselves in danger. Obviously, there were some violent confrontations, I believe, in France with FEMEN ladies and some Muslims at some point. So, obviously people see that and they do react to it. But overall, I don’t think they are taken nearly as seriously here as they are in the West at present.

FEMEN and Pussy Riot – what is the connection there?

Natalya Antonova: Pussy Riot, when they did their protest in the country’s main cathedral, they had a very clear, a very explicit message. And I would argue that FEMEN have a much broader platform. They are not necessarily anti-Government, they also have their fingers in different pies. I did notice that of course after Pussy Riot members were jailed FEMEN did attack Russian President Vladimir Putin and Angela Merkel in Germany. So, obviously there is that connection. It is very clear that they are playing off each other in the public sphere.

I would say that for the Russians, for the Ukrainians, what’s been lost with FEMEN particularly is their attention to social issues. I remember, I think it was last year or maybe a year and a half ago, they did this great protest in Kyiv where they had a beautiful naked women. She was out somewhere in public, it was pretty cold, she was standing there and she had this sign “I have cancer and our Government is crap”. That is something that a lot of people can actually relate to. And they also see the contrast of course. She is using her beautiful body.

She is still able to display her sexuality there. But you get the sense from that whole image, from that setup that she is actually dying and, of course, she is criticizing the country’s healthcare system by doing this. And that I think to a lot of people in Eastern Europe and post-Soviet landscape – that is more powerful than some of the political stuff there are doing because it addresses real concrete problems.

It addresses the issue of cancer patients not getting enough drugs and not getting enough pain medication, for example. Looking at it now, looking at this whole idea of sextremism that they’ve been pushing, I would say that the real sharp social criticism it is getting lost in more pop-culture stuff.

London

Feminists have been long saying the same thing - all issues are women’s issues, you need to hear our voices.

Julie Bindel: I don’t see why feminists should be expected to speak to every single issue of social injustice. If you look at the civil rights movement, the anti-racist movement here in the UK, then you wouldn’t expect some of the campaigns to stop police brutality against black men in the street to then also address cancer patients in a failing hospital. You wouldn’t expect working class pioneers in unions looking to change aspects of working life for underprivileged people to then all of a sudden put that aside and start campaigning for issues to do with children.

So, it is really not fair when we are told that because every issue is pursuant to women and women are affected by that we should leave aside the sharp messages that we are still talking about decade after decade. The reason why we are still talking about rape, murder, sex trafficking, prostitution, domestic violence and other ills that are mainly affecting women is because they haven’t yet been sorted out. And that’s the reason why decade after decade we have to repeat ourselves and think about new and more imaginative ways to tackle these issues because they are not going away.

And I think that the whole aspect of FEMEN’s campaigning which is – get your tits out for whatever cause – really, our collective breast have been exposed by patriarchy, by the pornographers, by sexism. We don’t need any more tits out for trafficking or any of those issues that you see movie stars getting themselves involved in, in order to use short tactics to get on the front pages of the newspapers. We need a whole social and cultural revolution which is about women being able to be closed, to not be exposed. We are in danger whether we wear dungarees or we walk around naked. What we need is to be taken seriously as women without having to bare our breasts.

Washington

Soraya L. Chemaly: I think what Julie is describing is something that I write about often, which is the safety gap in the developed world. It is important to realize that all the issues we are talking about, whether it is health or labour, or trafficking, or sexual and domestic violence – the level of physical insecurity that women experience in the world is far greater than the level of physical insecurity men experience. And that vulnerability in culture is impeding our ability to achieve parity and to have cultural equality that we really need to have in order to solve these problems.

So, in terms of a developed world the safety gap, which is a measure of how safe men and women feel, there is a gendered safety gap. In the US it is in the high twenties, which is a pretty big gap. And the more wealthier the nation is the bigger that gap is. That safety gap, it is really important to understand why so much of what we talk about has to do with women’s bodies because actually our bodies are subjected to the very high chance of violence, whether that violence is compulsory pregnancy, whether it is rape, whether it is domestic violence, whether it is just an inability to get the healthcare we need. But there is really no underestimating, just the basic need to get the safety gap closed and what that closing of the safety gap would represent overall.

Moscow

Last fall, as we ran up to our presidential elections, a number of political candidates made egregious statements dealing with rape, as a gift from God is the woman becomes pregnant and rape is an unfortunate way that a beautiful life can come to be. And voters become outraged and they went to the polls and actually punished most of those politicians. Is part of the problem of the need to recreate the wheel time and time again that politically women don’t get presentation?

Natalia Antonova: Yes. Especially in Eastern Europe, especially in post-Soviet countries, especially in a country like Ukraine the civil society is very underdeveloped and politics is essentially a boys club. You have someone like Yulia Timoshenko, who is still in prison by the way. The thing with Yulia Timoshenko is that people have used her to say – well, everything is cool with politics in Ukraine in terms of being a woman, if you want to be in Government – there you go. The thing is that she is not representative, she is a very visible minority. And when you don’t have ways in which you can be represented I think people tend to react against that in very extreme ways.

I actually think that FEMEN, that whole phenomenon, people have theorized in a number of ways – why are they doing this, who is behind it. There are all these conspiracy theories about it. But I think that they are feeling this void because for a lot of girls in Ukraine growing up… and I was born in Ukraine, even though I grew up in the States, I mean, I know what they are talking about when they say these girls, it is either turn yourself into a sex subject, or turn yourself into a sex subject who also has a political message. And that’s really the only two choices FEMEN says that women in Ukraine have. And I can see why a lot of women would actually think that way. As imperfect as the political system is, it engenders these kinds of extreme reactions because people really feel that there is no other way.

London

Julie Bindel: It is obviously better in the UK than it might be in other countries. And it is certainly worse in the UK than it is elsewhere. But there is no question that the political system is dogged by sexism. And we just have to see what’s happened recently in Australia with Gillard, we have to look at some of our female politicians who take a very strong feminist line on issues, such as the porn industry, such as prostitution and domestic violence, who are treated appallingly, who have comments made about their appearance.

For example one of our politicians Clare Short, when she was a Labour politician who was campaigning against the depiction of women in the tabloid press, had a house dotted with pictures of topless women. The newspaper sent down topless models to her house to taunt her. It was a shocking displace. And that of course will deter young women from going into politics. But it also gives a very clear message when a general public reads about this in the tabloid press that we are not really welcome. You have practical issues like there being barely any bathrooms for women in Parliament. You have issues such as long working hours and women being told that they can’t bring their children.

I would say that we should do what some of the Scandinavian countries have done and say “you know what? 50% of female politicians is a start”. But really, you need to be a bit more imaginative than equality, if you are a feminist. We don’t want to be on equal terms with men. We actually need to liberate ourselves from this patriarchal structure. And we need at least 70-80% of female politicians in order to start to address the horrific imbalance that has dogged us for centuries.

Washington

What do you think about this proposal?

Soraya L. Chemaly: What Julia is describing is really a normative change. All of our legislation, our policy, the ways that we have conducted what we do are normatively based on the experiences, bodies and life stages that men have. When we talk about representation, it is actually two things. One is, yes, it would be good if we had political parity at the very least. But two, what that really speaks to is this issue of experiential inputs.

Lots of studies show that women as legislators, regardless of their political affiliation approach problems differently. And so, there is a greater emphasis on economies of care, the things in terms of education or food, or work-family balance. Women legislators interact differently with their constituencies, they tend to be also more collaborative than hierarchical. We can’t achieve that in the US with 80% of our representatives being women. I mean, every single time I hear “era of the women” I just have to burst out laughing, we’ve been saying it for 30 years.

While it is great that in the last election we had record numbers of women elected to office, the fact remains that it is not even remotely near enough to what we need. Those women are doing amazing things and should be admired for the tenacity to do what they are doing. But really and truly, it is the same or a little less than it was 1924 I think. We are not a country that will ever institute gender equalities. And so, the ways in which we need to build alliances and confront norms need to take place differently.

The ERA for example has never passed, the equal rights amendment of 1975. It would basically say that discrimination on the basis of sex is not allowable. And that’s really disturbing to conservatives who since the early 1970s have said that that would lead to all kind of terrible things like co-ed schools and homosexuals getting married, and unisex bathrooms were a big deal. Anyway, that’s coming up again for ratification. 14th amendment doesn’t apply to women.

The thing is that laws can be changed, representatives change their minds, justices change their minds and a constitutional amendment extending equal protection to women on the basis of sex is not just culturally significant, but has practical application in term of, for example, women who sue for workplace discrimination… like the Walmart, over a million women sued Walmart and they actually can’t pursue their suit on the basis of sex as a class.

London

Would an equal rights amendment be passed in England?

Julie Bindel: We don’t have a great deal of good news to tell you. We’ve the equal pay act since the 1970s and we still don’t have equal pay. We have equalities legislation which translates into a better deal for some women, mainly middle class women and those who know how to use the system, and not for others.

So, we don’t have equality. I’ve always thought actually that striving for equality lacks some imagination. You actually have one man in the room and one women in the room, he’ll get more attention, he’ll speak louder. If it is in a workplace and you have one male colleague and one female colleague, he’ll get promoted above her, she’ll not get proper maternity benefits if she has children and may be sexually harassed, and she certainly may not even be employed in the first place.

We’ve tried it the old-fashioned way to see if women are actually promoted and hired, and treated well and equally on their merits, and they are not. But I think that what we need to look at now in our political system is that you can’t possibly have an equal playing field if you have exactly half of all women politicians because the men will shout louder, the men will get promoted, the men will make more of a fuss and the men will behave in a way that is pursuant to the power there are assigned at birth. So, we definitely need to strife for more than that. And I really hope that you in the States do better than we have in our equal rights legislation. And it is not to say it is not important to drive it through, but it really is only a start, and it is a very slow start.

Moscow

In Russia, is there a hope that equality will be achieved?

Natalia Antonova: Yes, I think there is. And that is the old Soviet legacy, I have to say, because when the Bolsheviks first came to power they actually fought quite radically for women’s rights. Today, paid maternity leave, it is not necessarily a reality for all the women, but it is enshrined in law. For example, I had my child in Russia, in Moscow and I had paid maternity leave. If I had been working in the States, it would not have happened.

You can find previous Live Panels here.

Via: voiceofrussia.com

Short link:

![]()

![]()

![]() Copy - http://whoel.se/~d4X3c$43i

Copy - http://whoel.se/~d4X3c$43i