(Corrects to remove any reference in paragraphs 47 and 48 to

historical buildings being destroyed)

By Natalia Zinets and Richard Balmforth

KYIV, June 4 (Reuters) - A large digital clock, inexorably

counting down to the kick-off of the month-long Euro 2012 soccer

feast, looks out onto a broad Kyiv boulevard where metal

barriers are going up to corral Europe's football faithful.

This is a giant pedestrian 'fan zone', where outside screens

will enable thousands of spectators to satisfy their soccer

hunger through the month of June.

The epicentre of the Euro invasion will be Maidan

Nezalezhnosti (Independence Square), a place of bubbling

fountains and a soaring statue to independence. It is Kyiv's

throbbing heart.

The last time thousands of people massed here in these

numbers was in the winter of 2004-5 when the Maidan was 'ground

zero' for the Orange Revolution protests.

That upheaval brought, for a while at least, a realignment

of political forces in the former Soviet republic.

The square rang then to the oratory of Yulia Tymoshenko. At

the losing end of her fiery rhetoric was Viktor Yanukovich,

whose suspect election as president brought tens of thousands

onto the streets.

Seven years later, after a reversal of fortune, she is down

- serving a jail sentence for alleged abuse-of-office as prime

minister. He is up, and in power as president.

But all this is a footnote in a city, where Russian

orthodoxy was born and whose 1,000 plus years of existence has

been marked by occupation, poverty, famine and flight.

History is so close here that you can almost reach out and

touch it.

Khreshchatyk boulevard - a tree-lined avenue which runs

north-south and leads into the Maidan - hems football fans in

with its heavy, Soviet architecture.

It was destroyed in 1941 by Red Army forces retreating

before the Nazi offensive.

Buildings like the cavernous central post office were a

product of Josef Stalin's reconstruction after World War Two

victory and the return of Soviet power.

So, forget the pub crawl for an hour or two and catch some

history. There'll be plenty of terrace cafes en route where you

can stop off for refreshment.

PROTEST CAMP

Leave the southern end of the 'fan zone' and you will see a

tent encampment stretching 50 metres (yards) along the pavement,

emblazoned with white flags bearing a red heart, and posters

calling for Tymoshenko's release.

This is a round-the-clock vigil by her supporters who say

they will stay there until Tymoshenko - in jail since last

August - has been released: history-in-the-making.

At the next intersection, turn right and there is a glossy

brown statue to Bolshevik revolutionary and Soviet state founder

Vladimir Lenin, his jaw jutting forward in a resolute pose.

Though the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union and Ukraine's

independence consigned communism to the dustbin, Lenin's

monument can be found in other Euro match cities in Ukraine.

But, apparently judged too un-cool for today's average

European tourist, his image has been air-brushed out of official

Euro promotion publicity.

Head up the poplar-lined Shevchenko boulevard, a steepish

climb in one of Europe's hilliest capitals.

Beware of the name. It's the Smith and Brown of Ukraine.

Soccer-mad though the Ukrainians are, this pleasant avenue

is not named in honour of the national team's top goal scorer

Andriy Shevchenko, but after 19th century poet Taras Shevchenko,

the father of Ukrainian literature.

Revered as the man who turned a peasant tongue into the

language of verse, Shevchenko's zeal in promoting Ukrainian

earned him both fame and disgrace with Russia's tsars.

Today in Ukraine he is the national symbol of the struggle

for freedom. The heavily-whiskered, avuncular Shevchenko stares

solemnly down from a pedestal in a park at the crest of the

hill, across to the garishly-crimson walls of the national

university which bears his name.

ER ... ANYTHING ON AT THE OPERA?

Proceed right along Volodomyrska street which is roughly

parallel to the Khreshchatyk. At the next intersection, you come

to the National Opera House.

Completed to a Viennese taste at the start of the 20th

century, Kyiv's opera house these days pumps out a regular fare

of Russian empire hardy annuals such as "Swan Lake" and "The

Nutcracker".

It is renowned too for being where the tsarist prime

minister Pyotr Stolypin was assassinated in 1911. He was shot in

the interval of a production of a Rimsky-Korsakov opera.

Kyiv's opera officials don't intend putting up any cultural

competition on Euro match nights, though Tchaikovsky's "Iolanta"

is showing on June 8 when the first tournament matches are

played in neighbouring Poland.

The street is named after Prince Volodomyr - more commonly

known to history by the Russian version of his name, Vladimir -

who ruled what was then called Kyivan Rus from 980-1015.

A convert to Christianity, he marched his subjects down to

the Dnipro where he had them dump their pagan idols and join in

a mass river baptism. It marked the birth of Russian Orthodoxy

which then swept east across Russian territories.

A few hundred metres along the street are the Zoloti Vorota

- Golden Gates - which back then marked the perimeter of the

city-fortress and its main entrance through which its rulers

marched majestically.

A thriving hub of commerce, Kyiv was a regular target for

invading hordes and the city was finally razed by the Mongol

Tatars in the 12th century. Little remains today of the original

ramparts, apart from two massive stones, housed in a museum.

It was Volodomyr's successor and son, Yaroslav, who codified

customs into basic law and hence became known as Yaroslav the

Wise. The 'hryvnia' currency, now back today as the coin of the

country, was first minted under him.

Further along Volodomyrska, though, is Yaroslav's even

greater triumph - the spectacular golden-domed St Sophia's

cathedral. He built it in thanks for a significant victory over

tribal raiders and its Byzantine, frescoed interior managed to

withstand turmoil and war over the centuries.

Ravaged by time and neglect, it has benefited from the

benevolent hand of former president Viktor Yushchenko, most

nationalist of the four leaders who have run Ukraine these past

20 years. He promoted much of the internal restoration work

during his four years in power.

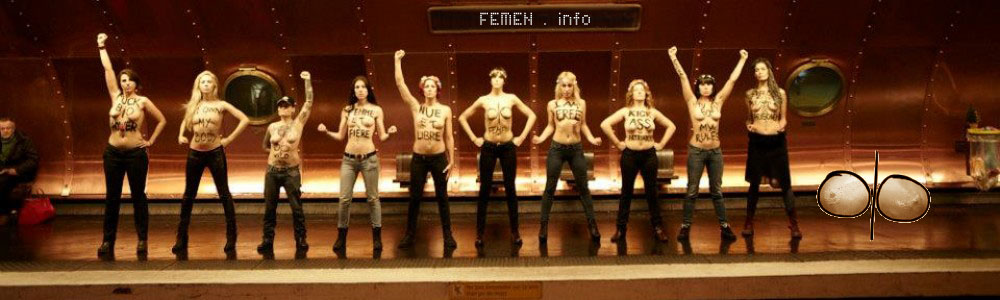

The cathedral still comes in for unwanted attention. A few

months ago, the young women of Femen - a neo-feminist protest

group and no respecter of conventional custom - climbed into its

bell-tower and staged a topless demo to further their cause.

GULLIBLE FOOL?

Silhouetted against the skyline in front of the cathedral is

the bronze figure of a mace-touting warrior on horseback. This

is Bogdan Khmelnitsky, a 17th century Cossack leader who racked

up notable victories over the Poles, the great enemy of the day.

In 1654 he signed a landmark treaty uniting Ukraine with

Russia as a bulwark against the Polish king. To this day,

Ukrainians cannot agree on his place in history. Many reproach

him for opening the door to centuries of domination by Russia.

Beyond him, are the blue walls and golden dome of St

Michael's, a mediaeval monastery named after the city's patron

saint, which was demolished by Stalin in the 1930s but

reconstructed after independence.

At its main gates, an information board details the Great

Famine or Holodomor ('death by hunger') of the early 1930s - a

catastrophe in which millions of Ukrainians died of starvation

in a policy directed by Stalin against the Ukrainian peasantry.

Yushchenko, who was disdained in the Kremlin as an obsessive

nationalist during his four years in power, spent much energy

seeking international recognition of the famine as genocide and

won support from several world governments.

But Yanukovich, less troubled about righting historical

wrongs, has shown little interest in the issue since he took

over from Yushchenko in 2010. A law defining the Holodomor as a

deliberate act of genocide remains in force, however.

KYIV'S ANSWER TO MONTMARTRE

Facing the monastery, do a quarter-turn to your left and

head for Andriyivsky Uzviz (Descent), a picturesque

Montmartre-style cobbled street lined with souvenir stalls,

street artists and arts and craft studios.

The Church of St Andrew, built in the 18th century in

baroque style by the Italian architect Bartelomeo Rastrelli,

stands at the top of the half-mile winding street, which drops

down to the city's riverside quarters.

You can pick up here Ukrainian crafts such as hand-made

embroidered peasant shifts, bead necklaces and wooden kitchen

ware as well as a mass of Soviet memorabilia.

Also drop in on the house-museum of Russian writer Mikhail

Bulgakov - best known for his mystical classic "The Master and

Margarita". He was born in Kyiv though he ended his days in

Moscow on the wrong side of the Kremlin.

Only a month ago the Descent itself was a sea of mud and

rubble as builders raced against time to put in new drainage. It

is a tribute to Ukraine's determination, but it was not without

controversy.

A separate development just off the street by a company

owned by Ukraine's richest man, steel and coal tycoon Rinat

Akhmetov, prompted street protests by members of Kyiv's cultural

community in April.

ESTA holding says that no 19th century buildings or any

building of historical and cultural value was destroyed in the

development of what is now planned to be the site of a cultural

centre.

Once down in the riverside quarter of Podil, head back

towards the city centre keeping the Dnipro to the left and after

passing some chic restaurants and drinking spots you find

yourself at the foot of a funicular.

A 1.50 hryvnia ticket will whisk you back up the hillside

you have come down and land you at the back of St Michael's from

where there are some clear views over the Dnipro and its islands

where Kyiv residents love to hold barbecues in the high season.

After checking out the view, go back to the cable car

entrance and take a track that plunges down into the woods.

Follow the path skirting the hill and, in a clearing, you

suddenly come to a majestic monument to the Christian Prince

Volodomyr, holding a cross aloft and facing the Dnipro where he

carried out his mass conversions.

Retrace your steps a bit and then take a path off left up

the hillside back to the main observatory point over the Dnipro.

From there, head down a tree-lined avenue to the main road

and turn left to drop down to European Square. You have

completed the loop back to the 'fan zone'.

The soaring, winged Monument to Independence comes into view

as you walk back to the Maidan. The stroll through the centuries

with Kyiv's historical forebears has taken a couple of hours.

Time for a borsch beetroot soup and a beer.

(Writing By Richard Balmforth, editing by)

Via: reuters.com

Short link:

![]()

![]()

![]() Copy - http://whoel.se/~AerPW$13n

Copy - http://whoel.se/~AerPW$13n