Whether she's railing against the Catholic hierarchy or battling social conservatives, Ukrainian activist Inna Shevchenko's feminism is a contact sport.

PARIS -- Heads turned toward Inna Shevchenko, the 22-year-old Ukrainian leader of the militant feminist group Femen, as she strode into the

brass-and-mirrors environs of the café where we had agreed to meet, on the central rue Pierre Lescot, one evening in mid-February. Atop the six-inch high

heels of her black felt boots, her wavy, strawberry blonde hair spilling out from beneath a black baseball cap, her eyes mint-green and penetrating, she

cut an impressive figure. Femen professes to use female beauty as a weapon, and Shevchenko is well armed.

We exchanged greetings and I ordered us a bottle of Côtes du Rhône. Over the next five hours, she would take only infrequent sips. In her tremolo Russian,

she told me that she gets her highs from demonstrating, not alcohol, and had tried vodka only "four or five times." She then complained about being sick

with a cold. "I'm not used to being sick." She was supposed to tell me about her personal life, but our talk first turned inevitably to Femen's latest, and

some would say, most unsuccessful, démarche of dissent, which took place on February 11.

That's when things turned sour for Femen, and for Shevchenko in particular. Within the space of a few hours, Pope Benedict XVI announced his resignation,

and, coincidentally, the French National Assembly approved a bill legalizing gay marriage - a Femen cause célèbre, at least since Shevchenko arrived in

Paris last August to establish the group's international branch. She decided to fête both events with a coup d'éclat that would prove

controversial even for Femen, already known for enacting daring, profanity-laced topless demonstrations involving physical confrontations that almost

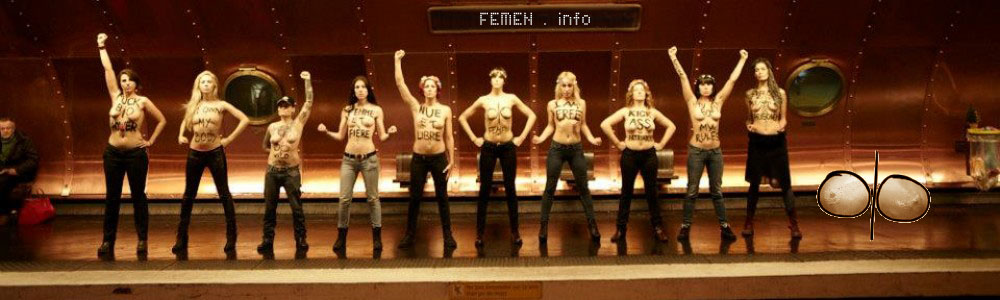

always end in arrests and, at times, in beatings for the participants. That afternoon, she led seven of her cohorts - all French women in their twenties

clad in nondescript overcoats - onto the premises of Notre Dame Cathedral, which was celebrating its 850-year anniversariy with an exhibit of newly forged

belfry bells. No mass was underway. As tourists milled about, the activists, having reached the nave, all at once stripped off their coats to reveal their

naked torsos, produced felt-wrapped sticks, and jumped the felt-rope barriers around the bells. "Pope No More!" they began chanting, administering

rhythmically timed blows to the bells, and halting after each strike, in choreographed fashion, to allow journalists (tipped off by Femen to attend) to

snap flash-photos in the gloom and illuminate the messages painted in black on their breasts and backs: POPE NO MORE! POPE GAME OVER! HOMOPHOBE DEGAGE! (HOMPHOBE GET LOST!), and BYE BYE BENOIT!

Security personal quickly set upon the activists. The choreography broke down, with the chaos mounting when the lights were cut, turning the cathedral into

a scream-pierced phantasmagoria lit only by flashing cameras. This afforded the nonplussed guards the chance, according to Shevchenko, to beat the women

(one of whom lost a tooth) and drag them out onto the square. There, she and her de facto French spokesperson, Julia Javel, 26, explained their act to

television crews as a celebration of the "homophobe" pope's departure and the adoption of the same-sex marriage law. Javel added a demand of a distinctly

feminist nature: that a woman ascend to the papacy.

The police arrived and a brief pro-forma detention followed. But soon after came unexpectedly harsh official condemnation of the group till then coddled by

much of the French media. Paris' mayor Bertrand Delanoë decried the protest as "misplaced" and "inopportune," lamenting it as an "act that caricatures the

fine battle for equality between men and women and pointlessly shocks a number of believers." Manuel Valls, France's interior minister, called Femen's romp

in the cathedral "futile," professed "consternation," and, though he holds office in a staunchly secular republic, offered his "support to the Catholics of

France who might have been insulted by this rude gesture." Even some in the liberal French press accused them of going too far. The national radio station

France Inter described the demonstration as "moderately clever" before opining that it recalled "a stupid provocation carried out by retarded adolescents."

And that was in Femen's defense.

But there was more. Monseigneur Patrick Jacquin, Notre Dame's rector, then announced that the cathedral may pursue Femen in court on three charges, civil

and criminal. Whether the French government decides to indict remains an open question, though it appears unlikely. In any case, in a Huffington Post (U.K. edition) blog

post, Shevchenko responded to Jacquin's threats with scorn and defiance, calling the cathedral's administrators "the modern-day Hunchbacks of Notre Dame"

and the "heirs to Torquemada," declaring their charges "as empty as the religion itself," and mocking Jacquin in particular as "tormented by forced

celibacy," and thus "not capable of distinguishing a woman's breasts from her sex organs," which amounts to professional "incompetence" for one employed by

an organization "regularly . . . enmeshed in various types of sexual and pedophilic scandals."

Shevchenko both thought up and led the protest, one more in a growing litany of theatrical, attention-grabbing assaults on "patriarchal society" that pit

half-naked young women against partisans of the sex industry, dictatorship, domestic violence, and the denial of equal rights for gays. She expressed no

regrets.

"Minister Valls spoke in favor of those who had their religious sentiments hurt by our act. Well, we [in Femen] view [religious] tolerance as a sickness."

She paused. "When I cut down the cross in Kyiv" - the act, carried out in support of Pussy Riot, that angered Ukraine's president and led to physical

threats against her and her flight abroad - "France was the first country to approve. But in France, a secular country, it's too much to demonstrate inside

a church? Here we have freedom of expression. So I expressed myself freely about religion." She paused again. "Why doesn't anyone think of my feelings as

an atheist? For me the cross is a symbol of the bloody Inquisition. Anyway, how can Notre Dame be considered holy? You see all these peddlers there, people

walking around with their potato chips and Cokes. It's a business."

(In fact her words described the scene in front of, not within, the cathedral. But she was not far off the mark. In centuries past the Catholic Church sold

gullible parishioners get-out-of-purgatory-early indulgences. Now, inside Notre Dame, church workers hawk crystal crosses for 250 euros and small,

unadorned commemorative bronze bells for, yes, 850 euros. Who apart from marketing consultants would consider 850 years an "anniversary?")

Shevchenko continued. "Our protest did one thing: it stripped the French of their masks and showed what their so-called progressivism really is. Their

reaction was purely Catholic. Their liberalism is just a cover-up, there's nothing behind it. It's all fake." This is strong, uncompromising

anti-Gallic verbiage from one who is petitioning the French government for political asylum. Was she worried that such words, to say nothing of a criminal

conviction, might adversely affect her chances?

"I'm not a slave to papers. I came here to carry on my work, not for the sake of a residency permit...I won't give up demonstrating. Now, when

everything looks really bad for us, is the best time to start a fight!"

But fallout has not been limited to potential legal jeopardy. As we talked, her cell phone beeped with messages containing threats from religious and

nationalist fundamentalists. A few days earlier, a nationalist group had sent her a (funereal) bouquet of flowers, with a minatory note: "Today we send you

flowers. Tomorrow we send you something else."

"Were you scared?" I asked.

"We laughed. We thanked them for the donation and used the flowers for the wreaths we wear on our heads."

Nothing in this soft-spoken young Ukrainian outwardly calls to mind the aggressive leadership role she has developed for herself within Femen since joining

it in 2010. She is warm and earnest, seemingly egoless about her appearance, and averts her eyes and smiles uncomfortably when confronted by those praising

her or expressing concern for her welfare. Such manners may stem at least in part from her modest provenance. She hails from Kherson, a small town in

southern Ukraine, where she enjoyed a childhood "like that of all girls. I was brought up as a typical Ukrainian, Slavic girl, and was taught not to shout

or argue." She was a patsanka (tomboy) who felt special affinity for her father, a socially conscious military officer who was hoping she would be

a boy. But though chauvinistic relations between the sexes are the norm in Ukraine, her father's word "was not law in the family. I could always go to him

and we could discuss things. He and I love each other and understand each other better than my mother and I do." He nurtured a sense of

independence. "The first time I took him my grades, he said, 'you're studying for yourself, not for me.' He didn't want to see them, and told me, 'You'll

answer to yourself for what you do in life.'" Both her parents support her Femen activism, especially her father. "He's proud of me, though he complains

that he learns more about me from the news than from me."

The 2004 Orange Revolution in Ukraine opened her eyes, giving her evidence that mobilized anger over a government's abuse of power could lead to positive

political change. "I was just a girl then, but for the first time I understood that we could have democracy in our country." She followed the proliferation

of talk shows that pitted politicians against journalists, who "looked more intelligent, so I wanted to be one." She soon moved to Ukraine's capital to

study journalism at the prestigious Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, from which she graduated with honors, and where she led the student

government. That extracurricular activity put her in touch with deputies of Ukraine's parliament, the Verkhovna Rada, and, eventually, with the mayor's

office of Kyiv, where she landed a job in the press bureau. "But they expected me to only write good things about them. It was torture. My mom said, 'just

accept it!' as most Ukrainian women would. Because it was extremely rare for a Ukrainian woman to be supporting herself financially and living

independently, as I was doing."

A callous offhand remark made by Ukrainian Prime Minister Mykola Azarov -- that political reforms "aren't a woman's business" -- prompted her to join Femen

and begin protesting. She lost her job as a result. (She had already become acquainted with two of Femen's founders, Anna Hutsol and Alexandra Shevchenko,

through vKontakte, a popular social networking site in the formerly Soviet sphere.) Before that, she thought little of feminists, whom she characterized as

"older unattractive women with a bad name in Ukraine, women who are dissatisfied with themselves and are always quarreling. Feminism had never been popular

and was considered something vulgar. I wanted to be an activist, not a feminist." Yet Femen would adopt the ideology, reconfiguring it as "pop-feminism," a

reductive catchall phrase that mostly stands for militancy, as well as a tactic, "sextremism," which Femen's web site defines as "targeted, extreme topless acts" of protest carried out in defense of

women's rights and equality for all. For Femen, feminism is a contact sport.

The writings of the early French feminist Simone de Beauvoir inspired Femen's originators. But for Shevchenko, reading Gene Sharp's activist handbook From Dictatorship to Democracy was a formative experience. She also fervently admires the late Greek art house filmmaker Theo Angelopoulos, and

said if she hadn't chosen to devote herself to Femen, she would have opted to make movies. But when I probed further, searching for other literary or

cinematic influences, she bristled.

"Femen is not based on a book, but on our experiences and lives as young women living in Ukraine. We had just had enough sexual harassment from guys, who

think if you go out with your hair done, you're doing it for them. But I don't hate men. I hate people against equal rights."

Though she didn't say so, the maximalist, Manichean spirit Femen brings to its struggle has obvious roots in the post-Soviet industrial and agricultural

wasteland that is Ukraine, as well as in longstanding traditions of radicalism reaching back into centuries of Russian imperial autocracy. At heart, she is

not an activist, but a revolutionary. What specifically accounts for the anger flashing in her eyes during demonstrations? An episode of personal suffering

or trauma?

"No. I've never been raped, I never was a victim of men. My consciousness was not raised by a blow from heaven or by a single event. It came gradually. My

anger grew, starting from the day the press office fired me for my activism, not for any work-related reason. The more we demonstrated, and the more I saw

how the police tried to stop us, the angrier I became. In each protest I went out to shout about what I couldn't stand anymore. When you see how hard

police try to stop you, you understand how right you are to be out there."

Nevertheless, one day in particular did set her irrevocably on the warpath. In December 2011, she and three other Femen members conducted a protest in

Minsk, in front of KGB headquarters, ridiculing Belarus's dictator Alexander Lukashenko.

Afterwards, as they were preparing to board a bus for Ukraine, agents from the security services seized them, handcuffed them, and drove them five hours

into the forest. All night, they subjected the women to beatings, taunts, and threats of murder. "They doused us in gasoline and lit lighters and walked

around us, threatening to burn us alive."

The experience radicalized her. "As I waited for death, I felt something changing inside. I realized that I could do nothing except continue with my

activism. I knew that if they asked me to beg them for my life, I would not do it. I was not ready to give up my struggle to save my life."

How does Shevchenko find living in one of Europe's most beautiful capitals? She shrugged at the question. "I don't know much about life in Paris. I really

don't care what city I'm in, I just need water and electricity to carry out my activism. New York, Kyiv, Paris, it's the same to me." She hasn't learned

French and shows little interest in the language. When I suggested that at least there was less sexism in France than in her homeland, she disagreed. "In

France, as in Ukraine, men make comments when I walk by, they try to touch me, they think they have the right to talk to me. There are so many falsities

here that are covered up. But you strip off the bandage and the pus gushes out. That's what we did in Notre Dame. We stripped off the bandage."

Shevchenko seems wiser than her 22 years. She spoke cogently, her manner understated, mature,

and yet, somehow, vulnerable. In her eyes and voice lurked a sadness. By accident I confirmed this when I asked her what sort of food she preferred.

"Chocolate," she responded. "I eat chocolate at night for comfort when I cry."

I was taken aback. "Cry? What do you cry about?"

She looked away. "Disappointments, you know . . . . Oh, I don't like answering such questions." She laughed nervously and took a sip of wine.

The way she spoke of her father told me she missed him. She has reason to be sad; she is unlikely to see him soon. Otherwise, she is, after all, a young

woman who had to flee her country, leaving behind her family, language, and culture. As we were preparing to call it a night I asked her where she saw

herself in ten years.

"I don't think about that," she replied flatly, fixing her mint-green eyes on mine. "I could be killed tomorrow."

Her beeping cell phone reminded her of that.

A couple of evenings later, at Cinéma L'Arlequin across the Seine on rue de Rennes, I attended the premiere of Nos Seins, Nos Armes!, a

documentary about Shevchenko and Femen shot for the television channel France 2 by the exiled Tunisian filmmaker Nadia El Fani and the prominent French

journalist Caroline Fourest

(Three other feature-length movies about Femen will be debuting at upcoming film festivals, including the one in Cannes.) So that we could go together, I

met Shevchenko and eleven other Femen activists at the Lavoir Moderne Parisien, the disused theater in the northern part of town that serves as their

training center. They stepped out into the frigid February night coiffed in their trademark flower wreaths, drawing looks from passersby, some startled,

others curious. The Notre Dame escapade had made them famous. In the metro, some passengers gawked, a couple of older men looked disgruntled and moved

away, others smiled. At the theater, camera crews and photographers awaited, along with a crowd of well-disposed spectators. The scene in the film showing

Shevchenko gripping the chainsaw and attacking the cross in Kyiv drew applause. During the standing ovation that followed the finale, she smiled almost

demurely, visibly ill-at-ease with all the approbation.

The crowd's positive reaction "is hard on me, not good. Once your ass is in a comfortable place, you're not a fighter anymore," she announced in English

the next day at Charlie Hebdo, the satirical magazine that won worldwide notoriety for publishing, in 2011, controversial cartoons by the artist

Luz depicting the prophet Muhammad, which led to the firebombing of their old office and police protection for some of the staff. Charlie Hebdo's

editor-in-chief, Gérard Biard, had invited Shevchenko and Femen to guest-edit the March 8 (International Woman's Day) issue.

Bespectacled and gentle, he likened Femen to the original "eco warriors," and told me their tactics (baring breasts among them) recall those once deployed

by the radical 1960s Mouvement de la Libération de la Femme. What first drew his attention to the group? "Femen picks its targets very carefully --

religious places, centers of political and social power and the patriarchy, the places embodying what they're struggling against."

Luz presented Shevchenko with the drawings he had just finished. She was not pleased.

"Why do you show us standing this way? Femen stands straight, holding posters high . . . . We are more ugly, I don't want us to look sweet. We never look

sweet." She summed up her advice for revisions: "More scandal! More violence!"

Javel laughed, adding, "One of us is going to be killed. That will be a big scandal!"

After the editing session and the departure of Shevchenko and Javel, Luz remarked, "It's strange for us to have a girl come to Charlie Hebdo and

tell us there's not enough violence, not enough scandal. We're stuck in comfort. When Inna comes here, she brings us out of comfort."

Biard takes seriously the threats Shevchenko has been receiving from fundamentalists of various sorts. "She is clearly exposed. It takes only one crazy

person and . . . ."

Threats hardly deterred Russian revolutionaries of centuries past, and doubtless will not intimidate the Ukrainian Shevchenko. Back at the café, when we

were discussing all she had been through since joining Femen, she declared, "Before, in my old life, I didn't want to be free or even know what freedom

was. Now I know I cannot live without it. All that has happened to me in the past three years has made me stronger. Once you have tasted freedom, you will

sacrifice everything for it. It's like a narcotic, in a good sense. You don't want to quit."

Via: theatlantic.com

Short link:

![]()

![]()

![]() Copy - http://whoel.se/~7kUWc$2OM

Copy - http://whoel.se/~7kUWc$2OM